Vanesa Vallejo reports in Pan Am Post about how high tax rates are driving companies out of Colombia.

Direct foreign direct investment in Colombia has fallen 37 percent as of February. Panama will be the recipient of some of this pullback.

Between 2015 and 2016, seven multinational companies have left. PayPal, Ripley and Mondelez are just a few of the bigger names.

Though many factors influence a company’s decision to withdraw investments from a country, it’s almost certain that high taxes and excessive bureaucracy are near the top of the list.

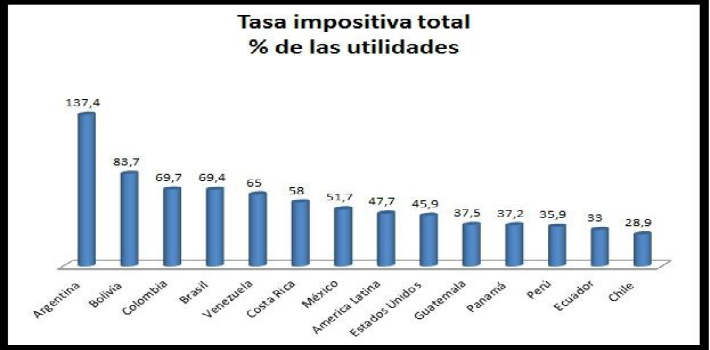

According to Doing Business 2016, 69.7 percent of a company’s profit go to the state of Colombia. That’s $70 of every $100 earned.

When deciding if they’re going to invest or not, companies look at the profitability of a project, which often depends on profit margins that take a serious hit with high taxes. High taxes discourage investment. Still, many insist on denying financial theory when they say taxes won’t bankrupt a company, or that companies have too much money, or that a little redistribution wouldn’t hurt.

Besides low taxes, companies need tributary stability. It eases financial forecasting and eliminates additional risk factors. This therefore raises the chance of investment project execution. Hence the president’s announcement on Twitter in response to different companies leaving Colombia.

However, this year’s studies for the reform have started despite Santos saying that if the peace accord passes, there would be no new taxes. Labor Minister Clara Lopez said if the accord is signed, taxes will have to go up to finance post-conflict activities. In Colombia, no low taxes, nor financial stability.

Another important issue when deciding whether to invest or not in a country is the ease of doing business. This criteria includes aspects like the amount of paperwork to create a company, or how easy it is to enforce a contract. Logically, companies will want to reduce expenses and time to establish a company. They also need an institutional framework that guarantees contract fulfillment and protection of property rights.

In this aspect, Colombia doesn’t offer the best conditions. According to Doing Business 2016, on average, a Colombian company must make 11 payments to the government. It spends around 239 hours doing this, while the average time in OECD countries is 176. Regarding contract enforcement, Colombia takes place 180 out of the 189 considered countries. A company in Colombia needs 1,288 days to enforce a contract. In Singapore, which ranked first, this takes between six and nine times less.

It should be clear that the Colombian tributary structure brutally punishes the productive sector. Also, cumbersome paperwork and lack of guarantees for contract enforcement, as well as tributary instability make Colombia an unattractive country for investment. It’s absurd that people keep demanding a raise in taxes with the excuse that they want to improve the country’s situation.

In Colombia, like any country in the world, private investment creates employment. Presenting a high tributary load to companies as a solution to poverty is asking for the path that has taken so many countries to misery. In Venezuela, for example, Hugo Chavez told private companies to “expropriate.” Back then, many Venezuelans and people all over the world applauded him and saw him as the poor’s benefactor.

We now see that expropriations and taking money away from companies is the worst thing a society can do. The only way to help the poorest ones is by creating jobs. We don’t need more public spending, but a government that doesn’t interfere with the actions of individuals and companies.