World currencies are in the news with devaluations happening around the world. I am putting together a collage of articles that I found interesting as they all came out this week. First there is an opinion by Andres Oppenheimer in the Miami Herald on what it means for Miami and perhaps Panama as Latin American currencies are being hit hard. The second part of this article is on the lighter side and comes from The Wall Street Journal on how “In Hong Kong, Inflation Worries Spook the Spirit World” and finally from Mauldin Economics and things that make you go HMMMMM, Money for Nothing, a trailer for a new documentary about the inner workings of the Federal Reserve. It looks at the level of their responsibility not only for the last crisis but, more importantly, for the NEXT one. The movie is screening across the US in September, and I urge readers to seek it out and support what is a very important film. Watch the trailer at the end and find out more about the schedule at the movie’s homepage.

But first here is Andres’s Opinion piece:

By Andres Oppenheimer

aoppenheimer@MiamiHerald.com

Judging from the Miami Herald’s latest headlines, home prices in Miami keep soaring and tourists from Brazil, Argentina and Venezuela keep flooding this city thanks to their countries’ strong currencies. The big question is how much longer the fiesta will last.

If you look at the latest economic figures, you may conclude that it’s about to be over. Latin American currencies have depreciated rapidly in recent weeks, making it more expensive for Latin Americans to travel and buy properties abroad.

Over the past month, Brazil’s currency fell by nearly 10 percent relative to the U.S. dollar. Brazil’s Central Bank announced Friday that it will inject up to $60 billion into the economy over the next four months to keep the Brazilian currency from falling further.

Over the past 12months, Brazil’s currency fell by nearly 22 percent relative to the U.S. dollar, Argentina’s by 21.4 percent, Peru’s by nearly 8 percent, Chile’s by almost 7 percent, Colombia’s by 6 percent, and Mexico’s by 1.4 percent, according to the Inter-American Development Bank (IADB).

In the Caribbean, Jamaica’s currency fell by nearly 14 percent and the Dominican Republic’s by 8.4 percent over the same period, the IADB says.

The depreciation of emerging countries’ currencies has accelerated since Federal Reserve chairman Ben Bernanke suggested June 19 that the U.S. economic recovery may allow the government to scale down its stimulus funds. That has led to the belief that U.S. interest rates will rise, and has moved investors to begin shifting money back from emerging countries to the United States, economists say.

Most international financial institutions tend to think that the decade of super-strong Latin American currencies has come to an end.

“The party is going to be over soon, if it’s not over already,” senior IADB economist Andrew Powell told me. “World interest rates that have been at historically low levels will not remain there; the growth rate of China in recent years is not sustainable, Europe still has its problems, and commodity prices will likely come down.”

The change could help Latin American countries in the long run, among other things because weaker currencies could make their exports more competitive abroad, economists say. But it will make their imports — as well as trips to Miami — more expensive.

“If the trend of depreciation of Latin American currencies of the past few weeks continues, we could see a drop in Latin American tourism and property purchases in the United States,” says Daniel Lederman, a senior World Bank economist specializing in Latin America.

But some private sector economists disagree, saying that they don’t expect a continued drop of Latin American currencies, nor a dramatic decline in tourism or real estate purchases in the United States.

“Miami shouldn’t lose any sleep,” says Alberto Bernal, head of research of Bulltick Capital Markets. “What we have seen in recent weeks is a normal correction within an ongoing boom.”

Bernal’s logic is that the fundamental factor behind Latin America’s strong currencies — the rapid urbanization of India and China, whose new middle-classes are consuming more Latin American commodities — remains unchanged. People in India and China will continue migrating to the cities for the foreseeable future, he says.

“This boom will end when China’s urbanization rate reaches 70 percent of its population, from the current 51 percent, and that process could last another fifteen years,” Bernal told me. “In the meantime, Latin America’s commodities will continue to be much coveted products.”

My opinion: I wouldn’t be surprised to see a further depreciation of Latin American currencies, especially in South America’s commodity exporting countries.

A recovering U.S. economy will draw more capital from emerging economies to the United States. And while China’s middle class will keep growing and consuming Latin American commodities, a trip to China a few months ago makes me wonder whether the country’s social tensions over corruption, pollution and other issues won’t result in political turmoil, and slower growth than currently expected.

Latin America’s commodity exporters should roll up their sleeves, increase productivity, draw investments and diversify their economies promoting non-traditional exports — all of which they should have started doing years ago.

Fortunately, many of them have built healthy foreign currency reserves, and have not incurred massive debts like the ones that led to the 1980’s financial crisis.

The party is over, but if they handle it well, it doesn’t need to be a traumatic awakening, neither for them nor for Miami.

In Hong Kong, Inflation Worries Spook the Spirit World

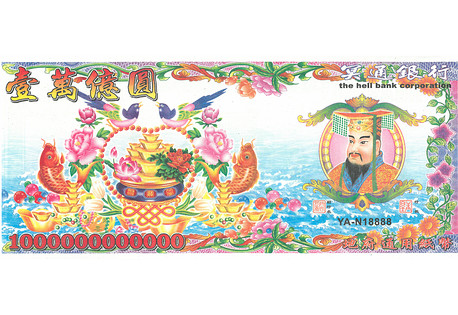

Yes a trillion dollar bill is now the most popular denomination as inflation has taken hold.

Deep in China’s spirit world, an inflation crisis is brewing that would give central bankers chills.

For hundreds of years, Chinese have burned stacks of so-called “ghost money” for their ancestors to help ensure their comfort in the afterlife. The fake bills resemble a gaudier version of Monopoly money, emblazoned with the beatific-looking image of the Emperor of the Underworld.

Traditionally, paper money burned in China came in small denominations of fives or tens. But more recent generations of money printers have grown less restrained. The value of the biggest bills has risen in the past few decades from the millions and, more recently, the billions. The reason: Even Hong Kong’s dead try to keep up with the Joneses, and their living relatives believe that they need more and more fake bucks to pay for high-cost indulgences like condos and iPads.

Photos: Hungry Ghost Festival

This year, on the narrow Hong Kong streets that are filled with shops that specialize in offerings for the dead, there appeared a foot-long, rainbow-colored $1 trillion bill. “What we have right now is hyperinflation,” says University of Hong Kong economist Timothy Hau. “It’s like operating in Zimbabwe.”

The inflation problem is expected to worsen during this year’s Hungry Ghost festival, when the gates of the underworld are believed to open and ghosts are allowed to wander the earth. For the next few weeks, residents across the city are staging traditional opera performances to entertain their supernatural guests (leaving the front row of seats empty for ghost spectators), cooking elaborate meals of roast meats for their enjoyment and burning wads of fake money on the sidewalks in their honor.

The inflation in the underworld mimics what is happening above ground. In recent years, both Hong Kong and mainland China have felt the impact of higher prices. With its rising cost of food and housing, Hong Kong in particular has its hands tied in fighting inflation, thanks in large part to its currency peg with the U.S. dollar, which keeps the city’s interest rates low.

The local funeral trade is feeling the pinch as well. In Hong Kong Island’s rapidly gentrifying western reaches, nearby the city’s ginseng and shark’s fin sellers, is a row of half a dozen funeral shops. Their shelves are stacked high with gaily colored rows of dim sum baskets, air conditioners and DVD players, all made out of paper and intended to be burned as offerings. Situated adjacent to a hospital and several coffin shops, these stores all offer items for the needy dead.

The shops have been around for decades, but one is shutting down next month. “The rent is so expensive, and it’s hard for us to carry on,” says the 62-year-old manager, Tony Tai.

“Inflation is everywhere, so of course it happens in the underworld too,” says Li Yin-kwan, 42. The $1 trillion bill is the most popular note in her shop, she says, “because it allows the ghosts to buy many things, such as a fancy car and a big house.”

Still, she said that there is also a place for burning smaller-value bills. “The ghosts need spare change to buy daily necessities, too,” she says, such as clothes and food. On a recent Friday, all the trillion-dollar bills in her shop and the shops next door were sold out. “I’m sorry,” Ms. Li said to one customer. “There are still some $100 billion notes left.”

Vendors like Ms. Li point to other worrying signs of an underworld economic crisis, including the proliferation of paper credit cards from the Bank of the Underworld—some adorned with pink diamond motifs and VIP stickers, and others colored mint green like American Express. Other symptoms of a splashed-out consumer economy are afoot, including paper iPads, flat-screen TVs with 3-D glasses and sports cars.

Economists say the problem is that the underworld has no control over how much currency enters its economy. The more “ghost money” burned, the more inflation continues to zoom upward. “Inflation is everywhere a monetary phenomenon,” says Mr. Hau, citing the late economist Milton Friedman. “It’s the money supply that’s causing it.”

He says that like Zimbabwe, the underworld should dollarize its economy and begin accepting mainly U.S. currency. Few people, he argues, would burn real dollars, reducing the amount of cash flowing into the spirit world.

Kenny Cheung, manager of 50-year-old funeral service company Cheung Kee, prefers to burn faux glasses of milk tea and Western suits made of paper for departed ancestors, such as his grandfather, because they are things he knows they would miss in the afterlife. “If your heart is strong, there’s no need to burn so much money,” he says.

While he does sell $1 trillion bills (HK$50, or about US$6.50, gets you a stack worth $100 trillion in underworld currency), as well as ghost money closely resembling U.S. greenbacks, he draws the line at paper credit cards. “I don’t think it’s a good habit for the living or the dead,” he says.

Hong Kong’s central bank, the Hong Kong Monetary Authority, says it is powerless to address underworld inflation because it lacks the regulatory authority. “As a result, [the HKMA] does not collect monetary statistics on the amount or value of currency in circulation in the ‘afterworld’ or seek to regulate its issuance activities,” said a spokeswoman, who apologized for not being funnier in her reply.

According to Chinese tradition, burning ghost money—which in many ways is more of a cultural than religious practice—is a vital part of ancestor care. The traditional view of the Chinese afterlife is that it closely mirrors the real world, with its own otherworldly bureaucracy full of officials that need careful cajoling—not to mention bribes.

“We’ve got corruption in the underworld as well,” says Maria Tam, Chinese University of Hong Kong anthropologist. For example, she says, if you burn a paper house for your ancestors, you have to burn money as well. “Otherwise some petty bureaucrat down there will probably take it for their own,” said Ms. Tam. “So you need money to bribe them.”

Cash is needed for other pursuits as well. “In the underworld, they also need money to gamble,” says Mr. Cheung. “No money, no fun.”

Now for some serious business – MONEY FOR NOTHING

Yes, it is time to invest in some hard assets my friends and Panama is a nice place to be right now. Hope that you can join me.

![[SB10001424127887324747104579023861625197646]](https://s.wsj.net/public/resources/images/OB-YP176_GHOSTF_D_20130820014231.jpg)

![[image]](https://si.wsj.net/public/resources/images/OB-YP127_GhostH_BV_20130819204640.jpg)