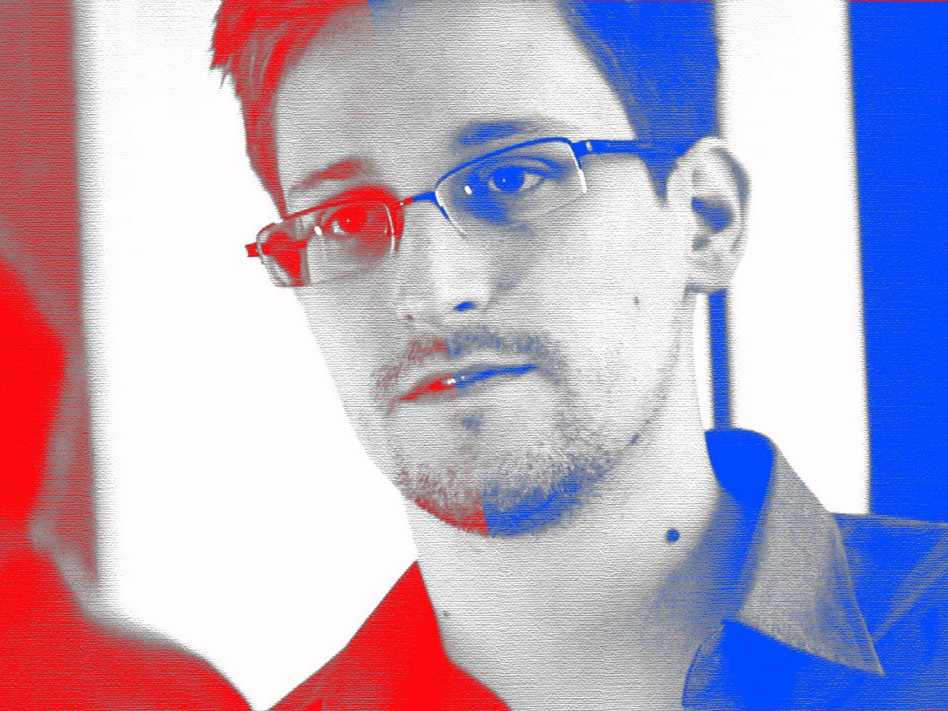

Here is an interesting article on Snowden as reported in Reuters. Edward Snowden requested political asylum of 20 or more countries across the globe to avoid facing espionage charges in the United States. Though he is now seeking temporary asylum from Russia, where he has been stranded in the Moscow airport, only a few nations, all in Latin America, have been openly receptive to his pleas.

By Peter Hakim

Reuters, July 17, 2013

No one should be surprised that Washington’s Latin neighbors are displaying such sympathy for Snowden. The U.S. history of abuse and insult still weighs heavy across the region. Latin American nations cannot resist the impulse to bring discomfort to their northern neighbor — which has regularly intervened to prop up repressive military regimes or rig elections, even as it touted its own democratic principles. Washington used its power to exploit the wealth of many other countries, while championing free markets. Fortunately, most of this is now history.

But bitterness and mistrust have clearly not disappeared — in part because abuses and insults continue. Every Latin American nation chafes at Washington’s punitive, and counterproductive, Cuba policy. The U.S. immigration debate is deeply offensive to Mexicans and Central Americans, and reminds them of past offenses. Washington’s drug policies are another source of antagonism.

No, it should not be a surprise that the Western Hemisphere is now home to a cluster of hostile U.S. adversaries, and even capitals friendly to Washington are often sympathetic to their views.

To be sure, only three of the region’s 20 countries – Bolivia, Venezuela and Nicaragua — said they would offer Snowden refuge (and one rather ambiguously). But several others voiced support for efforts to shield him from U.S. prosecution. Snowden, however, still might have been left without a single asylum offer, had Washington not pressed its European allies to close their airspace to Bolivian President Evo Morales’s plane — and thereby force his grounding in Vienna. Morales, on his way home from a meeting in Moscow, was suspected of carrying Snowden to safety.

Morales and other regional leaders were outraged — claiming, probably correctly, that Washington would never have done anything similar to the president of a European country or any large nation. The U.S. should be embarrassed by this episode.

The leaders of all three countries now promising asylum can each cite recent personal experiences of what they consider U.S. harassment. The late President Hugo Chavez of Venezuela was probably mistaken in blaming Washington for the 2002 military coup that temporarily ousted him, but the Bush administration later left no doubt that it welcomed his overthrow. During Morales’s first run for the presidency, in 2002, the U.S. ambassador warned Bolivian voters that his election would sour relations between the nations. Nicaragua’s President Daniel Ortega confronted a U.S.-financed guerrilla war against his revolutionary government in the 1980s, though Washington had long maintained ties with the brutal Somoza dictatorship he pushed from power. More recently, Washington backed Ortega’s opponent when voters returned the Sandinista leader to the presidency in 2005.

Yet, even with this history, until Morales’s plane was grounded, Bolivia was not considered a likely destination for the fugitive.

Once Bolivia opened its doors, however, President Nicholas Maduro Moros of Venezuela may have felt some need to assert his own nation’s leadership of Latin America’s anti-U.S. forces. Maduro acted even though Venezuela had, just weeks before, taken the initiative to repair relations with Washington. Secretary of State John Kerry met for more than an hour with Venezuela’s senior diplomat.

It’s not much of a stretch, however, to suspect that Maduro simply could not resist this unexpected opportunity go after Washington. This was a central focus of Chavez’s agenda — which the new president has pledged to pursue without change. Maduro also understood that an anti-U.S. gesture could only improve his precarious standing with Venezuela’s Chavista loyalists and lift his profile across the region as Chavez’s flag bearer.

Since Maduro was also at the meeting in Russia when Snowden landed at the Moscow airport, Russians may also have had some influence on Venezuela’s asylum decision. Moscow, as a strategic ally of Venezuela, supplies most of its heavy armaments. Venezuela offered the perfect solution to what had become a headache for Russia. Snowden would be out of Russia yet readily accessible and easy to monitor. The Cubans, who exercise considerable clout in Venezuela, may have weighed in as well. They certainly didn’t want to bring Snowden to Havana, which could have halted the promising new U.S.-Cuban talks about opening direct mail service and immigration. This is a top priority for Havana. Nicaragua was also ambivalent about providing asylum for Snowden — saying it would do so but only if “conditions were right.” Like most of the other 17 Latin American nations that ignored or denied Snowden’s request, Nicaragua now has too much at stake in its relations with Washington to put them at risk. Its economy, crucial for the future prospects of the Ortega-led government and its truce with the local business community, depends on U.S. investment and trade, and has benefitted from considerable U.S. foreign assistance.

Ecuador, a member of the international ALBA alliance (Bolivarian Alliance for the Peoples of our America) was once seen as a natural choice for Snowden, since the nation was already providing refuge for WikiLeaks chief Julian Assange at its London embassy. But its firebrand president Rafael Correa appears not yet ready to give up all hope of restoring the special trade privileges that are so vital to Ecuador’s flower and vegetable industries.

Other potential asylums also have too much to lose here. Argentina’s government, though an increasingly close ally of Venezuela and Bolivia, doesn’t want to add to the many complications that bedevil its relations with Washington, particularly since several potentially costly lawsuits involving the country’s bonds await decisions in U.S. courts.

Brazilian authorities quickly rejected any involvement in the Snowden affair — a position consistent with the country’s long-standing approach of avoiding confrontation in its international relations. Despite the genuine anger at U.S. spying, Brazil has more reasons than ever to maintain cordial ties with its largest foreign investor and second largest trade partner. The Brazilian economy is stalling and its politics remain uncertain after several weeks of massive protests. President Dilma Rousseff, moreover, is scheduled for a long-awaited state visit to Washington in October.

Washington, despite the vivid memories throughout Latin America of its misdeeds, still retains considerable influence across the region. But it is useful to remember that whenever the United States finds itself in a hole — it has probably contributed in some way or another to the digging.