On 26 June 2016, the new larger locks were opened in the Panama Canal. These new locks not only doubled the capacity of the canal but also raised the maximum ship size from 110 ft. wide, 1,050 ft. long, and 41.2 ft. deep to 180 ft. wide, 1,400 ft. long, and 60 ft. deep.

According to the Financial Times, these new locks allow for an estimated 79% of all cargo-carrying vessels to transit the canal – up from 45%.

It is no secret that I believe transport data is both a forecaster and validator of economic direction. And transport movements have slowed (indicating a slowing economy) since the beginning of 2019.

A recent Seeking Alpha post suggests that the widened Panama Canal is changing freight patterns, resulting in less rail traffic and more trucking. This post concludes:

The bottom line is that the widening of the Panama Canal is almost certainly driving a secular shift on domestic US freight patterns, as more seaport traffic goes to the East Coast followed by truck shipments vs. West Coast ports and then cross-country by rail.

The remaining question is, what are we to make of the decline in *total* freight volumes in the Cass Report? On the one hand, because the effect showed up in trucking vs. rail almost immediately, beginning in 2017, by now YoY comparisons in total traffic should not be distorted by the shift. On the other hand, cutting out the rail leg in transportation is a net loss to the total, although again, that presumably would have been true a year ago as well.

In short, the YoY total freight statistics from the Cass Freight report — down YoY beginning in December — argue that tariffs have had a significant negative effect, after several months of “front-loading,” although they may be overstating the effect to the extent that the secular shift in domestic freight patterns brought about by the widening of the Panama Canal is still ongoing.

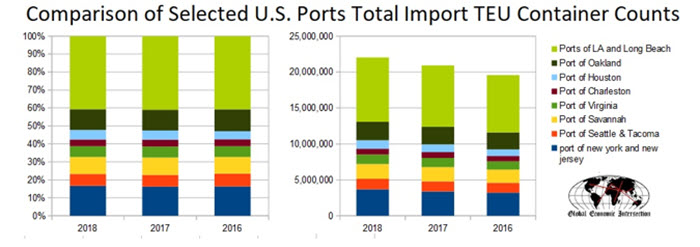

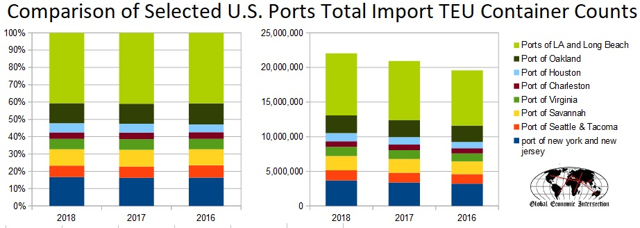

Of course, everything – including tariffs and the Panama Canal widening – affects the distribution system. The following graphic should clear up the effects of container movements due to the widening of the Panama Canal.

In short, it is difficult to see any noticeable effect of the widening of the Panama Canal on sea container imports. My take on the current state of logistics:

Evolution Vs. Revolution – From my logistics management background, supply chain modification has been going on since the beginning of time. Logistics engineers use quantitative analysis to design and build the infrastructure. The inputs to this analysis include labor (costs and availability), taxation, land costs, final users, energy, building costs, time elements, subsuppliers/sub-shippers, etc. Elements in this quantitative analysis change continuously – but once the investment is made, there is little one can do when it becomes uncompetitive except to shut it down. It is evident that the infrastructure for the movement of goods changes only gradually. A new potential supply route effects are evolutionary – and usually, take decades to fully implement. The transport system does not change overnight. After all, the Panama Canal is not free – and there are other ways to move goods by sea without using the Panama Canal.

Economic Shocks – This is when something happens that immediately affects logistics. Usually, this occurs due to wars (like the Gulf War completely disrupted sea transport in the Atlantic, Med, and Indian Oceans), supply disruptions (like the Arab oil embargo), major disasters, and some argue the tariffs with China. The opening of the Panama Canal in 2016 cannot be an economic shock that delayed its effect for two years to the beginning of this year.

The bottom line is that transport growth has been soft this year, and mirrors the softness seen in most economic sectors. It is illogical to assume there is a disconnect between the economy and the transport sector.