Last week the inaugural flight of Copa Airlines from Panama arrived in Barbados. This event was suitably celebrated by local authorities.

As I understand it, this was the culmination of years of work. The effort to have direct flights between Panama and Barbados was grounded in history; a history which recorded the blood, sweat and tears of many Barbadians: thousands of men and women who travelled to Panama and the families they left behind.

In 1984, Velma Newton penned a book from which I have borrowed the title of this column. That seminal work surveyed the contribution that Caribbean people made to the construction of the Panama Canal as well as the contribution these pioneers made to the local economies from which they were hewn.

Caribbean labour was cheap, plentiful and dispensable. Those qualities encouraged the builders of the canal to tap into this labour source, without which their venture might not be successful. The practice of using and discarding human lives that do not matter is not new.

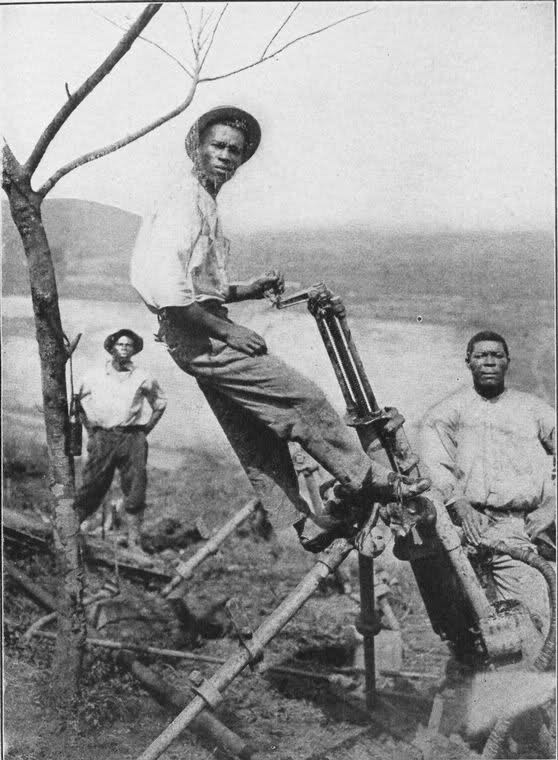

When it is placed within the context of its time, the idea of the Panama Canal was a tremendous feat of engineering and an example of the limitless potential of man, once he has confidence. The Canal is an artificial waterway, 51 miles long, cutting across the Isthmus of Panama and connecting the Atlantic and Pacific oceans. Given the technological limitations of the time, over a hundred years ago, a large labour force would have been indispensable.

But it was not only the need for numbers that led to the recruitment of Caribbean labour. Yellow fever and malaria were killing workers in large numbers and persons with other options were choosing not to sacrifice their lives there. Added to this, there were a large number of casualties caused by landslides and dynamite explosions used in the construction. Further, there were also frequent labour strikes that held up work on the project. Black Caribbean labour was the solution.

It is estimated that upwards of 40 000 Barbadians went to Panama between 1881 and 1914. Some estimates go as far as 60 000. If one were to imagine the exodus of 60 000 men of working age leaving Barbados now that would be mind-boggling. Some women went, but the vast majority who travelled were men in their physical prime. Given the size of this migration, there would hardly be a black Barbadian family that did not offer up a relative to the Panama trek.

This exodus tells us a lot about Barbados in that period. There was widespread poverty and few opportunities for black Barbadians. The local conditions were a push factor that made it necessary for Barbadians to leave their country in search of a better life. The wages in Panama were a great pull to that land.

Caribbean workers were not paid well there by any means, but it was far better than what they could make at home. They were paid less than their white counterparts and their living conditions were less salubrious than the white Americans who were also employed in the construction. Yet, these inferior condition in Panama were better than what was available to them in Barbados and the rest of the Caribbean.

I have heard vague stories of family members who travelled to Panama, but never returned to Barbados. Those who spoke of this venture have mostly passed, but even before then, they could give no information of what had become of those who travelled.

Many persons died while working on the canal, but many more survived and made new lives for themselves in that country rather than return to Barbados. They created families and their descendants became Panamanians, having no real knowledge of Barbados and their blood relatives here.

The investigation of ancestry has become important to persons in the western world. Black people in the Americas have been told that their history began with slavery. Nothing could be further from the truth, but many of us have bought that bogus story. As a result, when we trace our roots we are expecting to find an enslaved ancestor. Any slave in our family tree can be no more than an intermediate point in our history, for enslavement in the western world was no more than a brief episode in our long journey. But few of us have investigated what preceded that period. Deuteronomy 28 in our history book gives us a glimpse of how we got here.

Many Panamanians looking for some evidence of their ancestry may find that Barbados is an important part of their heritage. This island was the place from which their fore parents launched out to their now place of residence. Also of major importance, they would likely find that they have relatives still residing here. Copa, therefore, could be a bridge between not only countries, but generations of families.

One important barrier to closer relations between Panama and Barbados is language. This could turn out to be a stumbling block and merits immediate attention. Panama is primarily a Spanish speaking country. My experience has been that many professionals there speak good quality English, but this is not necessarily true across all classes.

On the other hand, very few Barbadians speak Spanish or have had any contact with that language outside of some rudimentary classes in secondary school. Travelling Panamanians would be more comfortable if they could communicate in their language when they come here.

Education officials have for years been telling us why we should learn Spanish. They had rightly recognised that given our geographical location and the language of many of our neighbours, Spanish should be regarded as an essential second language.

But they have also been telling us to learn French and Mandarin. This is not a bad idea, but it may be possible that this division of attention may have limited the thrust to make Spanish a more important language for us.

The Panama experience provided an important outlet for under-employed Barbadians and their remittances were the lifeblood of many families and an important buoy to the economy. One man’s meat is another man’s poison. Newton’s description of these emigrants as silver men discloses their second class status, for they were paid in silver while others were paid in gold, but that silver was important to Barbados. Copa may now allow this country to continue to benefit from the migration that began more than 100 years ago. We should be grateful for the foresight of those who fought for years to make this air connection a reality.

By: