I cannot believe the divide between the political parties and groups who live on entitlements, not only in the US, but around the world. This is a story of how the

Dutch deal with the realities of the situation, something to be learned by all. Here is a story I read in the Miami Herald.

By TOBY STERLING

Associated Press

AMSTERDAM — In the U.S., tax hikes have been the subject of partisan warfare that brought the country to the very edge of a “fiscal cliff.” In southern Europe, spending cuts have led to mass protests and labor strikes.

Maybe both could learn from the Dutch – whose compromise culture has kept the country afloat throughout the economic storm.

In the Netherlands, hits from the global financial crisis have so far been absorbed in a more relaxed way, as political parties, trade unions and officials have been more focused on cutting deals than in fighting over principles – and sharing pain as well as prosperity.

After all, the pragmatic Dutch outlook says, we’re all in this together.

The Dutch system, known as the “Polder Model,” seeks to divvy up the inevitable suffering from a downturn in a way that feels fair to all. Employers agree not to slash as many jobs as they otherwise might in exchange for workers agreeing to take pay cuts and not go on strike. The government, meanwhile, attempts to build public support for tax hikes and spending cuts by distributing them evenly across groups.

“Everyone is going to feel the pinch,” Prime Minister Mark Rutte said after a recent meeting with industry and union leaders, while adding: “We’re going to share the burdens as equally as possible. As a united country we’re strong.”

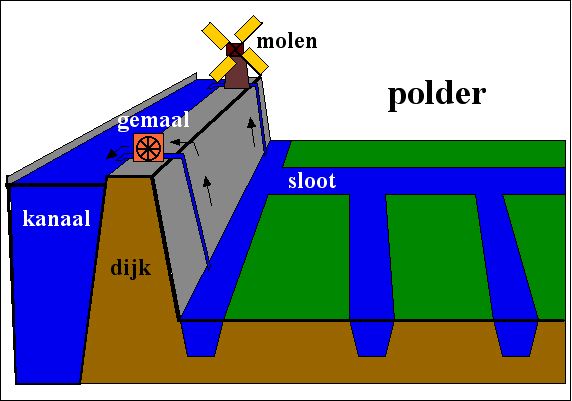

The idea of “Poldering” resonates deeply with the Dutch populace. Historically, dwellers of the low-lying country had to cooperate across social classes to share the costs of maintaining the system of windmills and dikes that protected them from floods and turned marshes into dry farmland known as “polders.”

It was a matter of life and death.

Now, with the economy in the doldrums, the housing market in decline and unemployment at a 10-year high of 7.2 percent, Poldering is back in vogue.

The new Dutch coalition government that took office in November consists of two parties who had been bitter foes for a decade: the conservative VVD party under Prime Minister Mark Rutte, together with the leftist Labor party. Their governing pact was designed to put the Netherlands on firmer financial footing by combining, for instance, the spending cuts on welfare desired by the conservatives with the tax increases on homeowners desired by Labor.

It’s as if the Republicans and Democrats had sat down together in Washington, hashed out their differences, and adopted the bulk of recommendations for long term budget reform in America.

Another source of Holland’s compromise culture is its long history of international commerce stretching all the way back to the Dutch East India Company – which dominated trade between Europe and Asia in the 17th and 18th centuries and was the first corporation to issue stock.

“Compromise is really in the nature of a nation that depends on international trade for its prosperity,” said Randall Filer, economics professor at Hunter College in New York.

“The intangible benefit is that outsiders – whether it be investors, or trade partners or political allies – trust it’s going to remain a stable country, with open markets and social stability.”

A sign of the benefits such openness can bring: The Netherlands is the world’s second largest agricultural exporter, after the United States.

The origin of the Polder Model in its modern form was an economic crisis in 1982: Amid high unemployment and stagflation, government ministers sat down with unions and industry leaders, and brokered a deal in which unions agreed to wage restraints and ended strikes in exchange for employment guarantees.

The Dutch economy, the fifth largest among the 17 eurozone countries, has been among the best-performing among industrial nations since then. According to IMF figures, it grew more than 1 percent per year faster than Sweden, France or Germany from 1990-2007, and slightly faster than the U.S. – but not quite as fast as Britain. Greece and Spain grew faster initially buoyed by the introduction of the euro, but their economies have since collapsed.

Major credit rating agencies say the Netherlands remains one of Europe’s few triple-A rated economies, although Standard & Poor’s this month repeated a negative outlook.

To help the Dutch government keep a handle on its finances, the first meeting between labor unions, employers’ associations and the new Cabinet in December yielded at least one concrete agreement.

The government said it would devote (EURO)100 ($133.5) to job retraining programs mostly for laid-off adults 55 years and older, currently the group having the most difficulty finding work, but also for unemployed youth and workers in the hard-hit construction sector.

Jose Kager, spokeswoman for an umbrella group of Dutch labor unions, said that the move was partly symbolic, given that workers stand to lose 10 times that much in long-term unemployment benefits under the governments’ current plans. But she said the talks will continue. Unions are not seeking to preserve all jobs, but rather to get the government and employers to agree to stop over-use of temporary contracts – which she said deprives workers of their shrinking safety net.

“It’s always better to have a seat at the table,” she said.