For years, the biggest nations have tried to to outsmart tax dodgers and reclaim trillions of dollars stashed in off-shore accounts. Many of them are tired of waiting and now just want to make peace and bring some of the money back home.

From Indonesia to Turkey and India to Argentina, several of the world’s 20 biggest economies are offering amnesties or incentives for citizens and companies to repatriate funds, some legal, others not. While U.S. presidential candidate Donald Trump wants a holiday tax rate to bring back some of the more than $2 trillion in income that companies have stockpiled overseas, Australia wants a tax to prevent profit flight.

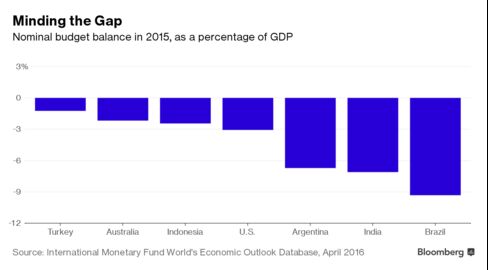

Some politicians are driven by a public backlash to perceived unfairness in global taxation as highlighted by the Panama Papers, others by the prospect of tighter tax rules agreed under the auspices of the G-20 group of nations. What all of them have in common is a need to bolster public coffers. Results so far have been mixed, with plans getting initial traction in Argentina and less so in places like Brazil.

“You’re smack in the middle of one of the greatest problems of international relations — the need for the state to get some control over what it thinks is its tax base,” said Jorge Braga de Macedo, former Portuguese finance minister and fellow at the Ontario-based Centre for International Governance Innovation. In light of G-20 members’ pledges to cooperate on tax evasion, there is “of course a degree of cynicism, but in the end it’s just national interest.”

On paper, the potential gains for public coffers are huge. In developing countries alone $638 billion in profits were shifted to tax havens in 2014, amounting to $172 billion in foregone revenue, according to an Oxfam study. Australia, which is struggling to maintain its AAA credit rating, lost about A$19 billion ($14.6 billion) of company profits to offshore tax havens in 2014 costing taxpayers up to $5 billion, according to Oxfam.

In response, Australian Prime Minister Malcolm Turnbull’s government is introducing a “Diverted Profits Tax” of 40 percent on multinationals shifting profits out of Australia. The tax will apply to companies with global revenue over A$1 billion and become effective July 1, 2017.

In the U.S., which has yet to emerge from 14 years of consecutive budget deficits, Trump proposes to impose a 10 percent repatriation tax. Currently, companies pay a top tax rate of 35 percent and can defer taxes on their offshore income until they decide to bring the earnings back to the U.S.

Stiglitz Critique

Days before Trump’s proposal, Nobel economist Joseph Stiglitz said that U.S. tax law allowing Apple Inc. to hold a large amount of cash abroad is “obviously deficient” and called the company’s attribution of significant earnings to a comparatively small overseas unit a “fraud.” Apple has firmly denied using any tax gimmicks, telling an EU tax panel in March that it had paid all of its taxes due in Ireland.

The Panama Papers data leak earlier this year fueled wide-spread anger at wealthy individuals and companies skirting the taxman, and prompted politicians to take action, said Macedo. “It was a wake-up call for states to do something. Transparency is key, otherwise only the fools pay taxes.”

In Turkey a proposal to allow tax-free repatriation of money is providing individuals “the last exit before the bridge,” said Finance Minister Naci Agbal in reference to the planned G-20 crackdown. “All countries are now passing regulations to bring back money held by their own nationals before 2018,” Agbal said in an interview last month.

G-20 Deals

G-20 and the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development have brokered several deals under which signatory countries agree to the automatic exchange of individuals’ financial transactions and to tackle “gaps and mismatches in tax rules to artificially shift profits to low or no-tax locations.” The agreements go into effect in 2017 and 2018. G-20 leaders meeting in Hangzhou, China Sept. 4-5, are expected to reaffirm the accords.

One reason why governments are offering incentives to repatriate funds at the same time they are preparing to crack down on evasion is because tax collection is more costly than getting voluntary compliance, said Linda Pfatteicher, a partner at Squire Patton Boggs LLP in San Francisco.

“It’s cheaper to raise revenue if people are voluntarily complying,” said Pfatteicher, adding that raising taxes from corporations may be harder than from individuals.

The success of getting multinationals to repatriate profits will depend to a large extent on the deal they’re offered, said Gary Hufbauer, a former U.S. Treasury official and fellow at the Peterson Institute for International Economics. “Companies don’t tend to bring money back to the U.S. if the repatriation tax is more than about 3 percent or 4 percent,” Hufbauer said.

The latest attempts to tap individuals’ wealth held abroad are showing mixed results. In Brazil doubts over legal guarantees on amnesty and deadlines to file have damped interest in repatriation. Indonesia recorded about 3.7 trillion rupiah ($280 million) declared in the first two weeks of an amnesty that runs until March 2017. It aims to recover 560 trillion rupiah. Many people ignored a similar program in 2008.

For a look at Indonesia’s tax amnesty, click here

In Argentina a tax amnesty involving bond purchases is off to a good start and attractive terms could lead Argentines to declare $100 billion to $150 billion, experts say.

Whether global coordination to squeeze tax havens and close loop holes will make much difference is equally uncertain, said Guntram Wolff, director at the Bruegel economics think tank in Brussels.

“G-20 coordination is loose at best,” Wolff said. “It’s not like there are strong inter-governmental instruments that can be used, where Chinese, European, Brazilian and Turkish authorities totally see eye to eye.”