Three new tree species have been identified for Panama. These are the plants Matisia petaquillae, Matisia changuinolana and Matisia aquilarum.

Botanists José Luis Fernández-Alonso, of the Royal Botanical Garden of Madrid and Ernesto Campos, research technician of the Smithsonian Institute of Tropical Research (STRI) of Panama, named a total of six new species of trees for science based on comparisons made to collections of dry plants from all over the Neotropics. Of these six, three of the new species have only been found in Panama and the rest in Colombia.

According to a Smithsonian report, the first two Panamanian species were named in reference to the places where they were collected and the third, Matisia aquilarum, found in Chagres National Park, was named in reference to the presence of a Harpy eagle nest in that tree, recorded by ornithologist Karla Aparicio and botanist Ruby Zambrano.

The new species from Colombia identified in the same report are Matisia genesiana, Matisia mutatana and Matisia rufula.

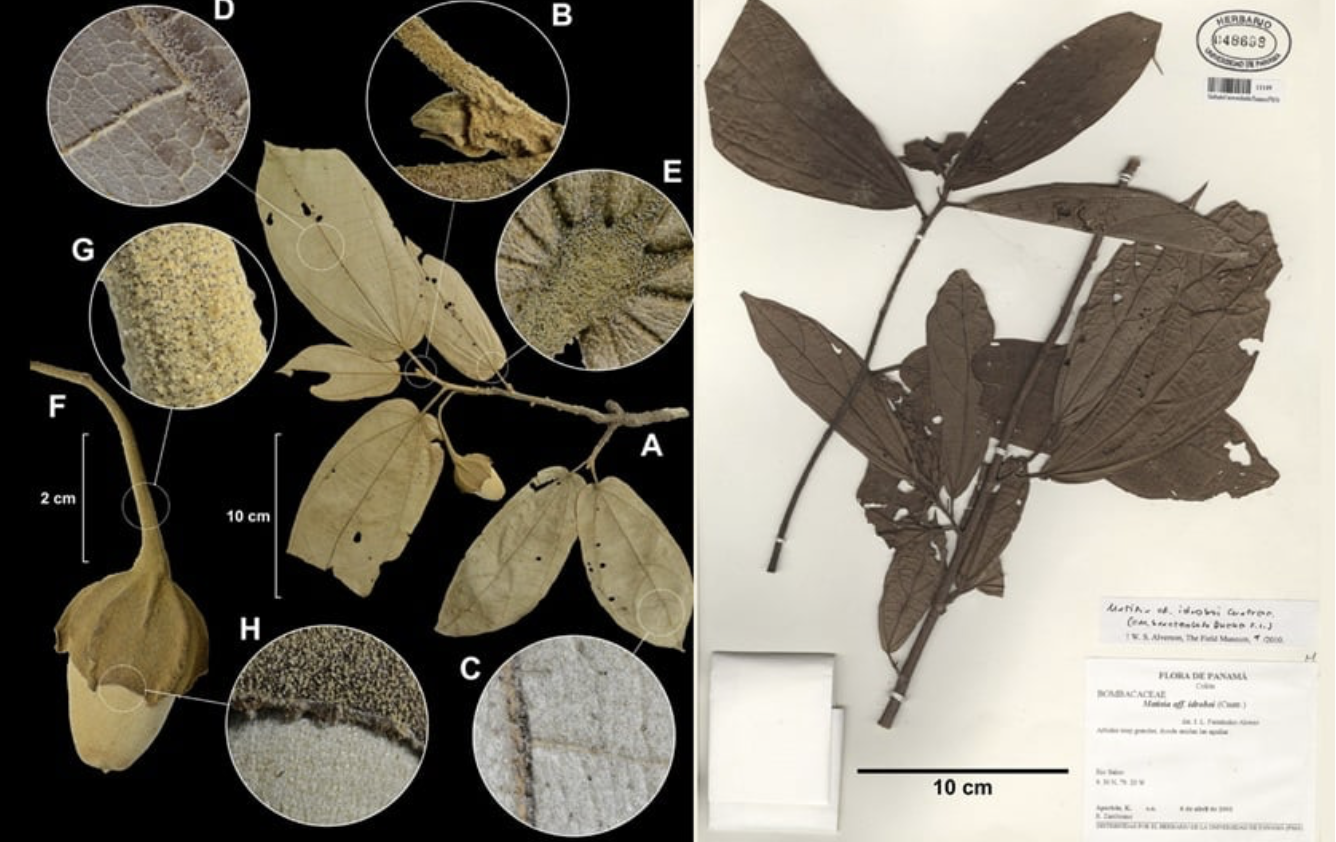

To determine this set of species, Fernández-Alonso analyzed samples of plants stored in herbariums in Costa Rica, Colombia, Ecuador and the United States. In Panama, with the help of Ernesto Campos, it was possible to complete the revisions of the collections of the Herbaria of the University of Panama (PMA), Summit Canal Zone (SCZ) belonging to STRI and the Autonomous University of Chiriquí (UCH).

In addition to the new contributions, the authors have included an updated dichotomous key of the species of Matisia for Panama in their manuscript. The last published identification key for Panama of this genus dates back more than half a century ago. Thus, the new one offers an updated tool for the correct identification and determination of species.

“In 2022 Fernández-Alonso contributed to confirm the identification of a tree, Matisia tinamastiana, from Cerro Trinidad in the Altos de Campana Forest Reserve and National Park, which turned out to be a new report for Panama,” Campos said. “This gave rise to the current collaboration.”

Botanists often collect large amounts of plants. The samples are dried, pressed between pieces of cardboard, and then mounted on a special cardboard and archived in the herbariums. Herbaria are specialized collections of dried plants, carefully stored in spaces with a controlled environment to preserve specimens in the long term. Currently, most specimens have online digital images that facilitate access and the exchange of knowledge.

But it depends on plant taxonomists to identify the samples. Plant specimens that cannot be easily identified can wait years until the expert in a particular group of plants compares the collections of the entire region and has the last word on whether a sample represents a species that no one has found before.

“Herbariums are not just collections of dried plants,” said David Mitre, research manager of ForestGEO-STRI in Panama, “they are a source of new information in the long term.”

Thanks to the collections carried out for decades, an expert was able to identify six new species. All belong to the family of plants, Malvaceae, whose common members include hibiscus (papo) and cotton… among many others. All also belong to the genus Matisia, whose members are found in Central and South America, up to Brazil.

“Discoveries like this remind us how important it is to make sure that protected areas are really well protected,” Mitre said.

The forests of Panama and Colombia are home to many species of plants that are not only important for the animals that live there, but can also be sources of new pharmaceuticals and other resources, of which we are not yet aware.

“The Smithsonian’s plant collections and our talented curators offer researchers around the world the possibility of correctly identifying plants,” says Joshua Tewksbury, Director of STRI. “This window to the world of plants allows the discovery of new drugs and makes it possible for conservationists to justify the protection of natural areas where rare species flourish.”