In the heated jungles of Central America in the early 1900s, thousands of workers toiled in the rain and mud trying to cleave Panama in half in order to join the Pacific Ocean with the Caribbean Sea. The difficult, dirty work involved more than digging and dynamiting, though. Working on the Panama Canal in the early days was about simply surviving.

But for all the groundbreaking engineering feats accomplished in creating the Panama Canal — one of the American Society of Civil Engineers’ seven Modern World Wonders — it was a decision that dealt more with man than machine that proved most critical.

Thousands of workers — perhaps as many as 22,000 — died while the French first tried to dig the canal. Yellow fever was rampant, as was malaria. On-job accidents killed and maimed. Close to 80 percent of the workforce was fleeing when the Americans took over the job in 1903.

When famed engineer John Frank Stevens arrived in 1905, his first job was to stop the carnage. And that meant accepting the relatively new idea that controlling mosquitoes — a measure favored by U.S. Army physician William Crawford Gorgas — would make the job site safer.

“Men of that era couldn’t conceive of a mosquito being able to kill a strong man. They just couldn’t respect that,” says J. David Rogers, a professor of geological engineering at Missouri University of Science & Technology. “The thing you had to conquer to make that project work was the sanitation issues.”

With Gorgas’ guidance and under Stevens’ orders, swamplands were drained and grasslands close to workers were cut to control the mosquitoes. Insecticides were used. Workers’ quarters were screened. Adult mosquitoes were captured. Quinine was administered to the men. The result: Yellow fever in the area was all but eradicated. And, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, deaths from malaria in the total population were reduced from a maximum of 16.21 per 1,000 in July 1906 to 2.58 per 1,000 in December 1909.

That medical success paved the way for the engineering marvel that followed.

Why Build the Panama Canal?

After seeing the relative success of another waterway — Egypt’s Suez Canal, which opened in 1869 — America envisioned a shortcut through Central America as a way of strengthening its position as a two-ocean power.

Before the Panama Canal opened, ships had to travel all the way around South America to get to the other side of the country. Soon after the USS Maine was sunk in Havana Harbor in 1898, the USS Oregon sailed from the West Coast around Cape Horn on the southern tip of Chile all the way to Cuba. The trip took 66 days. It would have taken around 21 days if the Panama Canal were operational and saved some 8,000 miles (12,874 kilometers) of travel.

For years, the U.S. had been considering building a canal through Nicaragua. But engineering concerns — not to mention worries about active volcanoes in the area — prompted President Teddy Roosevelt to continue with the failed French site in Panama instead. In 1903, he agreed to pay the French $40 million (it’d be about $1.2 billion now), and the Americans assumed control of a project that would take more than a decade to complete.

“The French [who had helped build the Suez Canal in Egypt] didn’t realize how massive and complex this was,” Rogers says. “It was like two different worlds.”

As the Americans took control, the building of the Panama Canal became an audacious example of American ingenuity and know-how. “It was a national pride project,” Rogers says. “We just kept writing checks.”

By the end, the U.S. had shelled out some $375 million (somewhere close to $11 billion today). The project came in some 444 percent over budget.

The Hurdles Faced

Besides the deadly diseases that plagued the early days of the construction, the difficult weather (tropical rains and intense heat) and the costs, engineers debated the very nature of the Panama Canal early on. They finally abandoned ideas about a sea-level canal (like the Suez), with Stevens instead insisting upon a series of locks that would raise or lower ships as needed. But that design necessitated construction of another big project.

Gatun Dam, at one time the largest dam in the world, had to be built across the sometimes-raging Chagres River to ensure the proper flow of water between the Pacific Ocean and the Atlantic. That formed Gatun Lake, a major component of the canal’s operation (more on that below).

And then there was the sheer scope of the project: Between the French and American builders, some 7.2 billion cubic feet (268 million cubic yards) of earth and rock had to be excavated, three times what was removed to build the Suez Canal. Most of the muck was placed onto railcars, shipped to the coasts and dumped into huge piles in the ocean. It now forms breakwaters and the foundation for towns and a military base. Much was dumped into the adjacent jungle, too.

“The efficiency in earth-moving was staggering,” Rogers says. “The earth had never seen anything like that before. And it didn’t afterward for a long time.”

Also a continuing problem: landslides. Yet despite the constant challenges, the Panama Canal opened in August 1914, with the SS Ancon becoming the first ship to officially make the trip through.

“They had to learn a lot while they were going,” Rogers says. “They used up all of the vitrified clay pipes to be produced in the United States, and all the cement produced in the United States, and all of the dynamite produced in the United States. All over this 10-year period, all diverted down to Panama.”

In its first five years, decreased traffic because of World War I and a series of landslides (which closed the passage for almost all of 1915 and would continue for years), the canal was barely used. That would soon change.

The Panama Canal was traveled extensively by U.S. warships in World War II, and now has become a major shipping route between East and West.

At one time, engineers again looked at making the passage a sea-level canal, which would eliminate the need for locks and decrease travel time. That idea was scrapped. After World War II, when military ships became too big to pass through, engineers also considered “nuclear excavations” — effectively, creating canals through the use of underground nuclear devices. That, too, was dismissed.

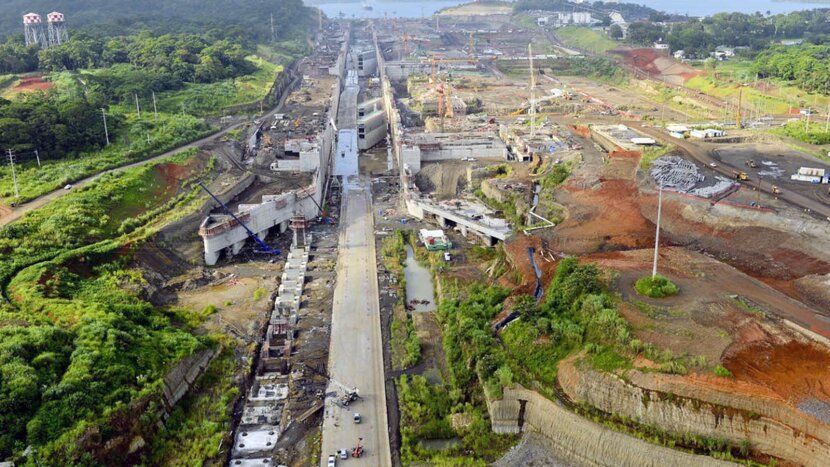

In 1977, the signing of the Torrijos-Carter Treaties returned control of the canal from the United States to Panama, effective Dec. 31, 1999. Since then, the Panama Canal has been expanded — the locks used to be about 100-feet (30-meters) wide; now they’re 175- to 185-feet (53- to 56-meters) wide — so that now even the biggest aircraft carriers and cargo ships can pass through.

How the Locks Work

The goal once a ship enters the Panama Canal is to get them up and over the terrain — and up 85 feet (26 meters) above sea level to Gatun Lake. That’s where the locking system comes in. A locking system was chosen for the Panama Canal design because the Pacific Ocean sits at a higher sea level than the Atlantic. So rather than excavating down to sea level, engineers determined that a series of massive locking gates that could raise ships above sea level into a large man-made lake (Gatun Lake) would be the best option.

Ships entering the Panama Canal from the Atlantic enter the first of three Gatun Locks, where the massive chamber fills with 26.7 million gallons of water. To fill the chamber with water and raise the ship, the miter gates and lower lock valves are closed, while the upper valves are opened. The water from Gatun Lake rushes in through 20 holes in the chamber floor. It takes about eight minutes for the chamber to completely fill and raise the ship. The process is repeated two more times until the ship is level with Gatun Lake.

The ship then travels through Gatun Lake until it reaches the Pacific Ocean where it enters the Pedro Miguel Locks and the process goes in reverse — it’s lowered through two locks from Gatun Lake back to sea level. The entire trip — from the Atlantic Ocean to the Pacific — takes an average of 8 to 10 hours.

The ships don’t go through the Panama Canal for free. They pay a toll based on the measurements of the vessel each time they enter. And it earns Panama more than $2.5 billion a year. The 50-mile (80-kilometer) long canal hosts nearly 14,000 trips a year, mainly by container ships and others carrying fuel, coal, grains and minerals/metals, though other small ships make the crossing, as well.

Now, more than 100 years after its opening, you can see why it remains an engineering wonder.