They came from all over, hoping to get rich, 300,000 of them between 1848 and 1855, changing California forever. Word of the discovery of gold at Sutter’s Mill in January of 1848 (“The Gold Bug,” Dec. 3, 2020) got out slowly, and most of the prospectors that first year — a few thousand at most — came from California itself, Oregon Territory and the northwestern Mexican mining districts. But in 1849, they arrived in the tens of thousands from the Eastern states, from Canada, Britain, Chile, China and Australia. And Europe: 1848 was Europe’s “Year of Revolutions,” and many came to escape the subsequent turmoil, to find gold, freedom and new lives. All told, some 100,000 gold-seekers arrived in California in 1849, of whom 40 percent were non-American.

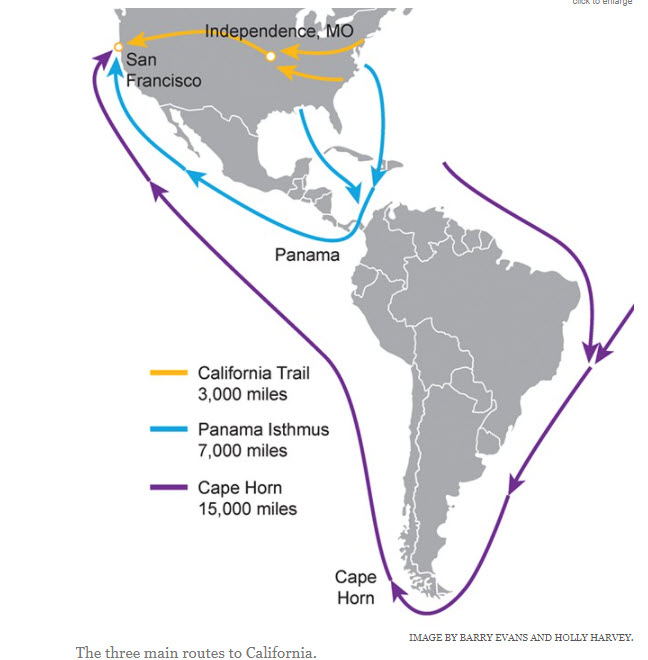

Other than those who came across the Pacific, three main routes were available to forty-niners coming from the East Coast or Europe: overland via Independence, Missouri on the California Trail; by sea to Panama, across the isthmus and again by sea to San Francisco; and around Cape Horn at the tip of South America. This week, we’ll focus on the Panama route; next week, Cape Horn.

Compared to going “around the Horn,” the Panama route cuts off 8,000 miles and several months of travel, although it also had its downsides: It was difficult to transport heavy equipment across the isthmus, while cholera, malaria, yellow fever and typhoid were rampant in that tropical climate. Landing in Chagres (near present-day Colon) on the Caribbean side, steamers from New York, Savannah and New Orleans disembarked hundreds of passengers at a time. The gold-seekers paid locals to paddle or pole them in shallow-draft cayucos to the town of Cruces, some 20 miles upstream on the Chagres River. From there, it took a minimum of four days — often much longer — to walk or ride mules to Panama City on the Pacific. This was the same mule track built in 1514 by people captured and enslaved by Spanish conquistador Vasco Núñez de Balboa, and that later served Welsh buccaneer Henry Morgan when he sacked Panama City in 1671.

Once there, would-be forty-niners had to wait for a steamer to take them to San Francisco. One entrepreneur who made the most of his enforced stay in Panama City was pioneer newspaperman Judson Ames, whose story is a saga in its own right. While publishing a paper in Baton Rouge, Louisiana, Ames heard about California gold and decided to go there to find whatever journalistic opportunities presented themselves. Arriving in Chagres with a 1,200-pound hand-printing press, he arranged for it to be loaded onto a barge, which promptly tilted over, dumping the press in the river. Somehow he was able to recover it, load it back on the barge and have it poled to Cruces, a trip that took a week. From there, he paid for a team of mules to carry the press, in pieces, to Panama City. Facing a three-month wait for available space on a California-bound ship, the opportunist set up his press and began publishing the Panama Herald. The following year, now in California, Ames started the San Diego Herald.

By 1851, five U.S. Mail Steam Line vessels were running from New Orleans to Chagres carrying up to 400 passengers at a time, with another eight steamers on the New York to Chagres run. All this traffic prompted construction of the Panama Railroad, which opened in 1855, shortening the trip from Chagres to Panama City by days or weeks. The 48-mile journey took just over an hour, as it still does today.

Get Vaccinated and stay safe!!