The canal is still awe-inspiring. Simon Veness goes along for the ride

A hundred years ago, a small ship set sail on a short voyage that changed the face of ocean-going navigation forever. The SS Ancon made the 50-mile journey in a lengthy 10 hours, but it represented a 7,800-mile saving on the alternate route from the Atlantic to the Pacific, a treacherous 30-day voyage. It also signified the culmination of 34 years of work, tens of thousands of deaths, the birth of a nation and the confirmation of a new world superpower.

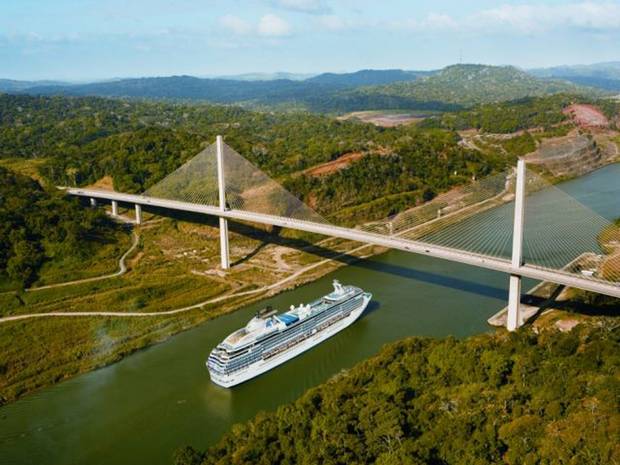

Today, the Panama Canal is every bit as awe-inspiring as it was at its official inauguration in August 1914, and it remains a major attraction more than 100 years after president Teddy Roosevelt was among the first tourists here.

Teddy was a shrewd, far-sighted politician and his insistence on building an alternative to the long passage around Cape Horn was the equivalent of John F Kennedy’s 1960s challenge to put a man on the Moon. After failed French efforts in 1880-1903, the US took over the project. It still took another 11 years to complete, but the finished work was fundamental to creating the Republic of Panama – originally a province of Colombia – and in marking out the US as the world’s most formidable force in maritime affairs.

No one knows exactly how many died in the course of the canal’s construction. The tragic and badly governed French expedition recorded at least 22,000 who perished – mainly to disease but also treacherous working conditions that included earthquakes, mudslides and equipment failure. The American dig accounted for another 5,609 deaths, in the process solving the 19th-century mysteries of how yellow fever and malaria were spread.

Chris Roberts, our onboard lecturer, provided the perfect introductory insight into our destination en route from Fort Lauderdale in Florida. We were sailing on the Coral Princess operated by Princess Cruises, a ship that is in many ways a Panama specialist, making multiple and partial transits each year. Ours was the “half way” voyage but it still afforded the full experience of the massive Gatún Locks and Gatún Lake at the “top” of Panama, the massive man-made lake whose waterflow effectively controls the whole lock process.

The ship’s ample deck space provided plenty of opportunity to witness the full splendour of the various locks we passed through in perfect close-up, both from the lofty perches of the Sports Deck, some 150ft above sea level, and at eye-level on the Promenade Deck, where you could practically high-five the occasional workman overseeing the huge, largely automated operation. With the water lowered, even our sea-going leviathan was dwarfed by the bulk of each chamber – they accommodate a staggering 25 million gallons of water at a time. Despite being built 100 years ago, the locks still work on the original simple principle, allowing gravity to fill a series of culverts that flow into and out of the locks, raising and emptying the water level of each one in turn.

The Coral Princess had arrived at the lower Gatún Locks at 5.30am on the fifth morning of a 10-night voyage, having already visited the southern Caribbean island of Aruba and frenetic Cartagena in Colombia, where a visit to the Old City and stories of pirates provided vibrant echoes of the Spanish Main. Now we were awaiting clearance to enter the first of the three locks that lift ships 85ft to Gatún Lake, which provides the conduit to the Pacific side and another three-stage lock process to return to the ocean.

At this early hour I was happy to observe from the comfy confines of our stateroom balcony, afforded a grandstand view without having to worry about pulling on more than a dressing gown to observe the initial process of the massive 50ft-high gates slowly opening to admit our bulk, with just two feet to spare either side. Unseen valves, ducts and chambers then swung into action below us, using nothing more than gravitational flow from the lake to fill the lock and elevate all 91,627 tons of Coral Princess smoothly to the next level. Attached fore and aft to electric “mules” – specially built two-way train engines that act as controlled guidance through each lock – we were carefully steered through.

This fascinating process was repeated twice more before the final gates opened to discharge us into Gatún Lake and its surrounding panorama of steamy forest and half-drowned islands. Howler monkeys and tree sloths vanished from the view of my binoculars as fast as I could find them; a rich birdlife added to the calls of a million frogs.

As beguiling as the wildlife might be, I was here for the canal and, happily, Roberts offered a regular narration for each stage of the transit, adding the appropriate key-notes of history as well as pointing out the occasional crocodile sunning itself on the banks.

There was plenty of time to absorb the full effect of floating on the top of the Central American isthmus – with all its oppressive humidity – before completing our lake meander and returning to the Caribbean in the afternoon (the full journey to Los Angeles takes two weeks) to sample the slightly dog-eared port of Colón.

We then headed for more Latin flavours in Costa Rica, where our call at Limón included a trip to a banana plantation and a flatboat cruise along the inland waterway, where more monkeys and sloths watched us go by.

The three-day return voyage to Fort Lauderdale gave me ample time to relax on the ship’s expansive decks and finish my essential reading for the journey, David McCullough’s The Path Between The Seas, which tells the full story of the canal, its failures, tragedies and triumphs. It also serves to underline a period of history that reads more like a novel and put our little day-jaunt around Gatún Lake in proper perspective. I might well have travelled much of the same route as those fearless adventurers who first mapped out the canal route in the 19th century but I experienced none of their deprivations and hardships.

Our own vessel was positively packed with mod cons and creature comforts, from the full-scale theatre to the choice of four restaurants and seven bars. Even the great Ferdinand de Lesseps, scapegoat for the French failure at Panama, probably never dined as well as we did. Nevertheless, as elegant and enjoyable as Coral Princess proved to be its vast structure was humbled by the immensity of the canal itself, an engineering achievement of persistence, toil, ingenuity and obstinacy.

De Lesseps started it, Teddy Roosevelt gave it new life and President Woodrow Wilson saw it completed. And we sailed blithely along it, giving thanks for a cruise experience that dwarfs almost all others.

Getting there

Coral Princess ( princess.com) sails to the Panama Canal on a round-trip from Fort Lauderdale each autumn, winter and spring, with occasional 14-night voyages to Los Angeles and vice versa. A typical 11-night voyage departs on 15 March, with an itinerary that includes Fort Lauderdale, Aruba, Cartagena, partial transit of Panama Canal to Gatún Lake, Colón, Limón (Costa Rica), Grand Cayman and back to Fort Lauderdale.