Just outside downtown Miami, in a luxury condo building made famous by the 1980s hits “Scarface” and “Miami Vice,” a billionaire ex-president is holed up in exile.

Ricardo Martinelli — scion of Panamanian landholders and an ex-Citigroup banker — was Latin America’s most popular president a few years ago, a leader who was just as likely to make headlines for helping his country win an investment-grade rating as he was for his lavish personal spending and extravagant parties. Yet as Panama’s Supreme Court was opening probes earlier this year into his role in alleged phone-tapping and corruption scandals that drained millions from government coffers, Martinelli skipped town. A separate investigation is now underway in crisis-torn Brazil, home to a company that won concessions for mega-projects in Panama during Martinelli’s 2009-2014 tenure, and one was also carried out in Italy.

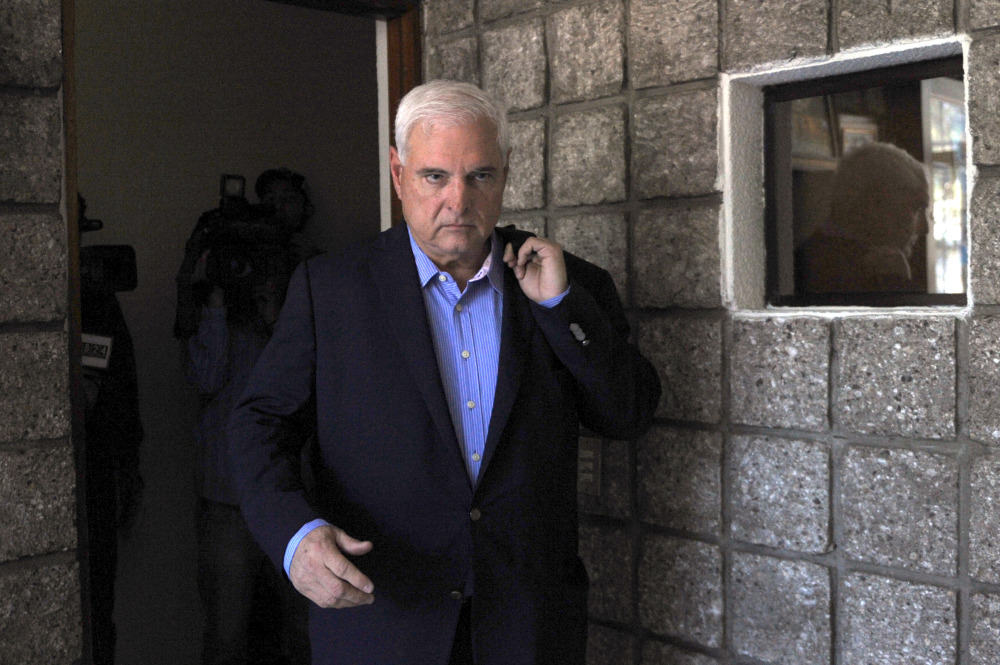

A silver-haired, portly 63-year-old, Martinelli spends much of his time in Miami’s waterfront Brickell neighborhood defending his public record, maintaining his innocence and hinting at a possible political comeback. He’s on Twitter constantly, tweeting opinions and announcements to his legion of 557,000 followers.

When he sat down for a recent interview at a Miami cafe, he was in a combative mood, lashing out at political enemies and rattling off his administration’s accomplishments — surging growth, falling unemployment and construction of Central America’s first subway. “We put Panama on the map,” he boasted. And then he laid out what essentially form the two central points of his response to the probes: Ricardo Martinelli has been a very rich man for a very long time; and rivals are using the investigations to weaken him.

Now it may seem strange for a politician caught in the middle of a corruption probe to be drawing attention to his wealth, but there’s a certain logic to the argument. Why would an already rich man steal from his country, he asks. The ex-president has a net worth of $1.1 billion, according to Bloomberg Billionaires Index. Top among his assets is the majority stake in grocery-store chain Super 99, with over $700 million in annual revenue. He also claims interests in banking, real estate, cement, media, energy and sugar, and owns a plane, two helicopters and a yacht.

“Everyone knows I have owned Super 99 for 30 years,” he said. “All my cases are political. There’s no evidence.”

Much of Martinelli’s ire is directed at his successor, Juan Carlos Varela.

Their ties stretch back decades. As young men, they ran in the same elite social circles and later became business associates in the rum industry. Both would enter politics after the U.S. toppled strongman Manuel Noriega in 1989. When Martinelli swept into office two decades later on a pro-business platform, he named Varela his vice president. Their relationship soured during those years, though, and by the time the 2014 elections rolled around, Varela was running against — and defeating — the Martinelli-backed candidate. Once in power, Varela undertook a push to root out corruption, part of a wave of investigations sweeping across Latin America as a faltering economic boom spurred demands for greater accountability.

Martinelli calls it a political vendetta, the price he’s paying for raising taxes on the rich — a “cardinal sin” in Panamanian politics, he says. Varela’s administration dismisses those comments.

“Ask the more than 150 politicians, civil society leaders, business leaders and journalists whose intimacy was violated by illegal telephone interventions if it is political persecution,” Álvaro Alemán, the president’s chief of staff, said in a written response to questions.

The phone-tapping case is one of two investigations that the Supreme Court has opened on Martinelli. The other centers on alleged corruption at his food-aid program.

In Italy, Martinelli was cited as a participant in a corruption scheme involving Panamanian contracts when a judge sentenced a man for attempting to blackmail former Prime Minister Silvio Berlusconi. And in Brazil, where the country’s massive kickback scandal is spreading overseas, prosecutors are lobbying Panamanian officials to turn over information that may help their investigation. A company at the heart of the scandal in Brazil, Odebrecht SA, also oversaw Martinelli’s subway project. The ex-president hasn’t been formally accused of any crimes in Italy and hasn’t been cited in the Brazilian probe. Odebrecht denies any wrongdoing in Panama.

“Martinelli left us a legacy of corruption, overspending and improvisation,” said Ramón Arias, head of Transparency International‘s Panama arm. The economic boom during Martinelli’s term — annual growth averaged 9 percent — was largely due to an expansion of the Panama Canal begun by his predecessor, he said. “The rest was mostly government spending. His model was plain old populism.”

Back in Miami, Martinelli is undaunted, mapping out his return one day to Panama and flirting with the idea of another presidential bid. While trying to keep a low profile, he’s still flashing some of those rich-and-famous spending habits that drew so much attention in Panama. He took up residence in Brickell’s iconic glass-facade building, a landmark in the area after appearing in the opening credits of the TV series “Miami Vice” and in a scene in the gangster movie “Scarface.” And a few months ago, a local Lexus dealer tweeted out a note congratulating him on a luxury-car purchase.

Martinelli’s more focused on his own tweeting campaign, though. His ability to connect directly to Panamanians, he said, has his political rivals on edge.

“They are so afraid of my tweets,” he said. “Look what happened in the Arab spring.”