Never Forget!!! Never Forgive!!!

The story first published on MSN was wiped clean this week by the media gestapo. Here it is from Esquire.

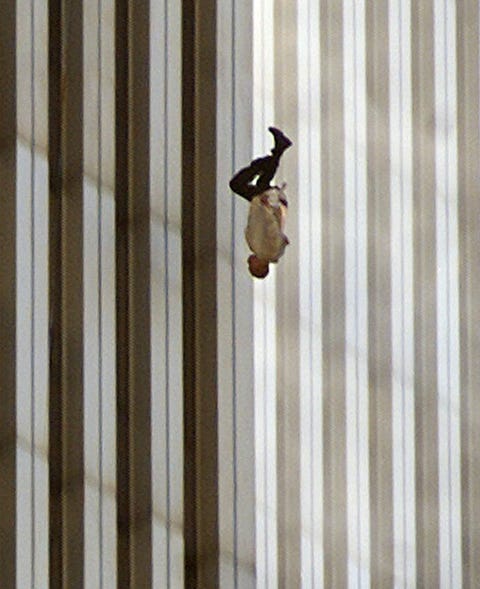

Do you remember this photograph? In the United States, people have taken pains to banish it from the record of September 11, 2001. The story behind it, though, and the search for the man pictured in it, are our most intimate connection to the horror of that day.

The photographer is no stranger to history; he knows it is something that happens later. In the actual moment history is made, it is usually made in terror and confusion, and so it is up to people like him—paid witnesses—to have the presence of mind to attend to its manufacture. The photographer has that presence of mind and has had it since he was a young man. When he was twenty-one years old, he was standing right behind Bobby Kennedy when Bobby Kennedy was shot in the head. His jacket was spattered with Kennedy’s blood, but he jumped on a table and shot pictures of Kennedy’s open and ebbing eyes, and then of Ethel Kennedy crouching over her husband and begging photographers—begging him—not to take pictures.

Richard Drew has never done that. Although he has preserved the jacket patterned with Kennedy’s blood, he has never not taken a picture, never averted his eye. He works for the Associated Press. He is a journalist. It is not up to him to reject the images that fill his frame, because one never knows when history is made until one makes it. It is not even up to him to distinguish if a body is alive or dead, because the camera makes no such distinctions, and he is in the business of shooting bodies, as all photographers are, unless they are Ansel Adams. Indeed, he was shooting bodies on the morning of September 11, 2001. On assignment for the AP, he was shooting a maternity fashion show in Bryant Park, notable, he says, “because it featured actual pregnant models.” He was fifty-four years old. He wore glasses. He was sparse in the scalp, gray in the beard, hard in the head. In a lifetime of taking pictures, he has found a way to be both mild-mannered and brusque, patient and very, very quick. He was doing what he always does at fashion shows—”staking out real estate”—when a CNN cameraman with an earpiece said that a plane had crashed into the North Tower, and Drew’s editor rang his cell phone. He packed his equipment into a bag and gambled on taking the subway downtown. Although it was still running, he was the only one on it. He got out at the Chambers Street station and saw that both towers had been turned into smokestacks. Staking out his real estate, he walked west, to where ambulances were gathering, because rescue workers “usually won’t throw you out.” Then he heard people gasping. People on the ground were gasping because people in the building were jumping. He started shooting pictures through a 200mm lens. He was standing between a cop and an emergency technician, and each time one of them cried, “There goes another,” his camera found a falling body and followed it down for a nine- or twelve-shot sequence. He shot ten or fifteen of them before he heard the rumbling of the South Tower and witnessed, through the winnowing exclusivity of his lens, its collapse. He was engulfed in a mobile ruin, but he grabbed a mask from an ambulance and photographed the top of the North Tower “exploding like a mushroom” and raining debris. He discovered that there is such a thing as being too close, and, deciding that he had fulfilled his professional obligations, Richard Drew joined the throng of ashen humanity heading north, walking until he reached his office at Rockefeller Center.

There was no terror or confusion at the Associated Press. There was, instead, that feeling of history being manufactured; although the office was as crowded as he’d ever seen it, there was, instead, “the wonderful calm that comes into play when people are really doing their jobs.” So Drew did his: He inserted the disc from his digital camera into his laptop and recognized, instantly, what only his camera had seen—something iconic in the extended annihilation of a falling man. He didn’t look at any of the other pictures in the sequence; he didn’t have to. “You learn in photo editing to look for the frame,” he says. “You have to recognize it. That picture just jumped off the screen because of its verticality and symmetry. It just had that look.”

He sent the image to the AP’s server. The next morning, it appeared on page seven of The New York Times. It appeared in hundreds of newspapers, all over the country, all over the world. The man inside the frame—the Falling Man—was not identified.

They began jumping not long after the first plane hit the North Tower, not long after the fire started. They kept jumping until the tower fell. They jumped through windows already broken and then, later, through windows they broke themselves. They jumped to escape the smoke and the fire; they jumped when the ceilings fell and the floors collapsed; they jumped just to breathe once more before they died. They jumped continually, from all four sides of the building, and from all floors above and around the building’s fatal wound. They jumped from the offices of Marsh & McLennan, the insurance company; from the offices of Cantor Fitzgerald, the bond-trading company; from Windows on the World, the restaurant on the 106th and 107th floors—the top. For more than an hour and a half, they streamed from the building, one after another, consecutively rather than en masse, as if each individual required the sight of another individual jumping before mustering the courage to jump himself or herself. One photograph, taken at a distance, shows people jumping in perfect sequence, like parachutists, forming an arc composed of three plummeting people, evenly spaced. Indeed, there were reports that some tried parachuting, before the force generated by their fall ripped the drapes, the tablecloths, the desperately gathered fabric, from their hands. They were all, obviously, very much alive on their way down, and their way down lasted an approximate count of ten seconds. They were all, obviously, not just killed when they landed but destroyed, in body though not, one prays, in soul. One hit a fireman on the ground and killed him; the fireman’s body was anointed by Father Mychal Judge, whose own death, shortly thereafter, was embraced as an example of martyrdom after the photograph—the redemptive tableau—of firefighters carrying his body from the rubble made its way around the world.

From the beginning, the spectacle of doomed people jumping from the upper floors of the World Trade Center resisted redemption. They were called “jumpers” or “the jumpers,” as though they represented a new lemminglike class. The trial that hundreds endured in the building and then in the air became its own kind of trial for the thousands watching them from the ground. No one ever got used to it; no one who saw it wished to see it again, although, of course, many saw it again. Each jumper, no matter how many there were, brought fresh horror, elicited shock, tested the spirit, struck a lasting blow. Those tumbling through the air remained, by all accounts, eerily silent; those on the ground screamed. It was the sight of the jumpers that prompted Rudy Giuliani to say to his police commissioner, “We’re in uncharted waters now.” It was the sight of the jumpers that prompted a woman to wail, “God! Save their souls! They’re jumping! Oh, please God! Save their souls!” And it was, at last, the sight of the jumpers that provided the corrective to those who insisted on saying that what they were witnessing was “like a movie,” for this was an ending as unimaginable as it was unbearable: Americans responding to the worst terrorist attack in the history of the world with acts of heroism, with acts of sacrifice, with acts of generosity, with acts of martyrdom, and, by terrible necessity, with one prolonged act of—if these words can be applied to mass murder—mass suicide.

In most American Newspapers, the photograph that Richard Drew took of the Falling Man ran once and never again. Papers all over the country, from the Fort Worth Star-Telegram to the Memphis Commercial Appeal to The Denver Post, were forced to defend themselves against charges that they exploited a man’s death, stripped him of his dignity, invaded his privacy, turned tragedy into leering pornography. Most letters of complaint stated the obvious: that someone seeing the picture had to know who it was. Still, even as Drew’s photograph became at once iconic and impermissible, its subject remained unnamed. An editor at the Toronto Globe and Mail assigned a reporter named Peter Cheney to solve the mystery. Cheney at first despaired of his task; the entire city, after all, was wallpapered with Kinkoed flyers advertising the faces of the missing and the lost and the dead. Then he applied himself, sending the digital photograph to a shop that clarified and enhanced it. Now information emerged: It appeared to him that the man was most likely not black but dark-skinned, probably Latino. He wore a goatee. And the white shirt billowing from his black pants was not a shirt but rather appeared to be a tunic of some sort, the kind of jacket a restaurant worker wears. Windows on the World, the restaurant at the top of the North Tower, lost seventy-nine of its employees on September 11, as well as ninety-one of its patrons. It was likely that the Falling Man numbered among them. But which one was he? Over dinner, Cheney spent an evening discussing this question with friends, then said goodnight and walked through Times Square. It was after midnight, eight days after the attacks. The missing posters were still everywhere, but Cheney was able to focus on one that seemed to present itself to him—a poster portraying a man who worked at Windows as a pastry chef, who was dressed in a white tunic, who wore a goatee, who was Latino. His name was Norberto Hernandez. He lived in Queens. Cheney took the enhanced print of the Richard Drew photograph to the family, in particular to Norberto Hernandez’s brother Tino and sister Milagros. They said yes, that was Norberto. Milagros had watched footage of the people jumping on that terrible morning, before the television stations stopped showing it. She had seen one of the jumpers distinguished by the grace of his fall—by his resemblance to an Olympic diver—and surmised that he had to be her brother. Now she saw, and she knew. All that remained was for Peter Cheney to confirm the identification with Norberto’s wife and his three daughters. They did not want to talk to him, especially after Norberto’s remains were found and identified by the stamp of his DNA—a torso, an arm. So he went to the funeral. He brought his print of Drew’s photograph with him and showed it to Jacqueline Hernandez, the oldest of Norberto’s three daughters. She looked briefly at the picture, then at Cheney, and ordered him to leave.

What Cheney remembers her saying, in her anger, in her offended grief: “That piece of shit is not my father.”

The resistance to the image—to the images—started early, started immediately, started on the ground. A mother whispering to her distraught child a consoling lie: “Maybe they’re just birds, honey.” Bill Feehan, second in command at the fire department, chasing a bystander who was panning the jumpers with his video camera, demanding that he turn it off, bellowing, “Don’t you have any human decency?” before dying himself when the building came down. In the most photographed and videotaped day in the history of the world, the images of people jumping were the only images that became, by consensus, taboo—the only images from which Americans were proud to avert their eyes. All over the world, people saw the human stream debouch from the top of the North Tower, but here in the United States, we saw these images only until the networks decided not to allow such a harrowing view, out of respect for the families of those so publicly dying. At CNN, the footage was shown live, before people working in the newsroom knew what was happening; then, after what Walter Isaacson, who was then chairman of the network’s news bureau, calls “agonized discussions” with the “standards guy,” it was shown only if people in it were blurred and unidentifiable; then it was not shown at all.

And so it went. In 9/11, the documentary extracted from videotape shot by French brothers Jules and Gedeon Naudet, the filmmakers included a sonic sampling of the booming, rattling explosions the jumpers made upon impact but edited out the most disturbing thing about the sounds: the sheer frequency with which they occurred. In Rudy, the docudrama starring James Woods in the role of Mayor Giuliani, archival footage of the jumpers was first included, then cut out. In Here Is New York, an extensive exhibition of 9/11 images culled from the work of photographers both amateur and professional, there was, in the section titled “Victims,” but one picture of the jumpers, taken at a respectful distance; attached to it, on the Here Is New York Web site, a visitor offers this commentary: “This image is what made me glad for censuring [sic] in the endless pursuant media coverage.” More and more, the jumpers—and their images—were relegated to the Internet underbelly, where they became the provenance of the shock sites that also traffic in the autopsy photos of Nicole Brown Simpson and the videotape of Daniel Pearl’s execution, and where it is impossible to look at them without attendant feelings of shame and guilt. In a nation of voyeurs, the desire to face the most disturbing aspects of our most disturbing day was somehow ascribed to voyeurism, as though the jumpers’ experience, instead of being central to the horror, was tangential to it, a sideshow best forgotten.

It was no sideshow. The two most reputable estimates of the number of people who jumped to their deaths were prepared by The New York Times and USA Today. They differed dramatically. The Times, admittedly conservative, decided to count only what its reporters actually saw in the footage they collected, and it arrived at a figure of fifty. USA Today, whose editors used eyewitness accounts and forensic evidence in addition to what they found on video, came to the conclusion that at least two hundred people died by jumping—a count that the newspaper said authorities did not dispute. Both are intolerable estimates of human loss, but if the number provided by USA Today is accurate, then between 7 and 8 percent of those who died in New York City on September 11, 2001, died by jumping out of the buildings; it means that if we consider only the North Tower, where the vast majority of jumpers came from, the ratio is more like one in six.

And yet if one calls the New York Medical Examiner’s Office to learn its own estimate of how many people might have jumped, one does not get an answer but an admonition: “We don’t like to say they jumped. They didn’t jump. Nobody jumped. They were forced out, or blown out.” And if one Googles the words “how many jumped on 9/11,” one falls into some blogger’s trap, slugged “Go Away, No Jumpers Here,” where the bait is one’s own need to know: “I’ve got at least three entries in my referrer logs that show someone is doing a search on Google for ‘how many people jumped from WTC.’ My September 11 post had made mention of that terrible occurance [sic], so now any pervert looking for that will get my site’s URL. I’m disgusted. I tried, but cannot find any reason someone would want to know something like that…. Whatever. If that’s why you’re here—you’re busted. Now go away.”

Eric Fischl did not go away. Neither did he turn away or avert his eyes. A year before September 11, he had taken photographs of a model tumbling around on the floor of a studio. He had thought of using the photographs as the basis of a sculpture. Now, though, he had lost a friend who had been trapped on the 106th floor of the North Tower. Now, as he worked on his sculpture, he sought to express the extremity of his feelings by making a monument to what he calls the “extremity of choice” faced by the people who jumped. He worked nine months on the larger-than-life bronze he called Tumbling Woman, and as he transformed a woman tumbling on the floor into a woman tumbling through eternity, he succeeded in transfiguring the very local horror of the jumpers into something universal—in redeeming an image many regarded as irredeemable. Indeed, Tumbling Woman was perhaps the redemptive image of 9/11—and yet it was not merely resisted; it was rejected. The day after Tumbling Woman was exhibited in New York’s Rockefeller Center, Andrea Peyser of the New York Post denounced it in a column titled “Shameful Art Attack,” in which she argued that Fischl had no right to ambush grieving New Yorkers with the very distillation of their own sadness … in which she essentially argued the right to look away. Because it was based on a model rolling on the floor, the statue was treated as an evocation of impact—as a portrayal of literal, rather than figurative, violence.

“I was trying to say something about the way we all feel,” Fischl says, “but people thought I was trying to say something about the way they feel—that I was trying to take away something only they possessed. They thought that I was trying to say something about the people they lost. ‘That image is not my father. You don’t even know my father. How dare you try telling me how I feel about my father?'” Fischl wound up apologizing—”I was ashamed to have added to anybody’s pain”—but it didn’t matter.

Jerry Speyer, a trustee of the Museum of Modern Art who runs Rockefeller Center, ended the exhibition of Tumbling Woman after a week. “I pleaded with him not to do it,” Fischl says. “I thought that if we could wait it out, other voices would pipe up and carry the day. He said, ‘You don’t understand. I’m getting bomb threats.’ I said, ‘People who just lost loved ones to terrorism are not going to bomb somebody.’ He said, ‘I can’t take that chance.'”

Photographs lie. Even great photographs. Especially great photographs. The Falling Man in Richard Drew’s picture fell in the manner suggested by the photograph for only a fraction of a second, and then kept falling. The photograph functioned as a study of doomed verticality, a fantasia of straight lines, with a human being slivered at the center, like a spike. In truth, however, the Falling Man fell with neither the precision of an arrow nor the grace of an Olympic diver. He fell like everyone else, like all the other jumpers—trying to hold on to the life he was leaving, which is to say that he fell desperately, inelegantly. In Drew’s famous photograph, his humanity is in accord with the lines of the buildings. In the rest of the sequence—the eleven outtakes—his humanity stands apart. He is not augmented by aesthetics; he is merely human, and his humanity, startled and in some cases horizontal, obliterates everything else in the frame.

In the complete sequence of photographs, truth is subordinate to the facts that emerge slowly, pitilessly, frame by frame. In the sequence, the Falling Man shows his face to the camera in the two frames before the published one, and after that there is an unveiling, nearly an unpeeling, as the force generated by the fall rips the white jacket off his back. The facts that emerge from the entire sequence suggest that the Toronto reporter, Peter Cheney, got some things right in his effort to solve the mystery presented by Drew’s published photo. The Falling Man has a dark cast to his skin and wears a goatee. He is probably a food-service worker. He seems lanky, with the length and narrowness of his face—like that of a medieval Christ—possibly accentuated by the push of the wind and the pull of gravity. But seventy-nine people died on the morning of September 11 after going to work at Windows on the World. Another twenty-one died while in the employ of Forte Food, a catering service that fed the traders at Cantor Fitzgerald. Many of the dead were Latino, or light-skinned black men, or Indian, or Arab. Many had dark hair cut short. Many had mustaches and goatees. Indeed, to anyone trying to figure out the identity of the Falling Man, the few salient characteristics that can be discerned in the original series of photographs raise as many possibilities as they exclude. There is, however, one fact that is decisive. Whoever the Falling Man may be, he was wearing a bright-orange shirt under his white top. It is the one inarguable fact that the brute force of the fall reveals. No one can know if the tunic or shirt, open at the back, is being pulled away from him, or if the fall is simply tearing the white fabric to pieces. But anyone can see he is wearing an orange shirt. If they saw these pictures, members of his family would be able to see that he is wearing an orange shirt. They might even be able to remember if he owned an orange shirt, if he was the kind of guy who would own an orange shirt, if he wore an orange shirt to work that morning. Surely they would; surely someone would remember what he was wearing when he went to work on the last morning of his life…..