Molas, a traditional textile craft, are made from layers of colored fabric that are stitched and cut using applique techniques to create patterns and pictures.

They originated in Panama, with the women of the Kuna tribe in the San Blas islands. But they have fans worldwide. They’re in museum collections from the Smithsonian to the British Museum, and have inspired textile artists and do-it-yourselfers.

The tradition is characterized by tiny, fine stitches, bold designs and bright colors. Early 20th century photos show Kuna women dressed in blouses and long wrap skirts decorated in the style. Over the decades, molas were increasingly marketed to tourists, and today you can buy not only mola blouses, with designs front and back, but also mola panels created as textile art for display. Handmade, authentic Kuna molas are labeled as such to distinguish them from imitations.

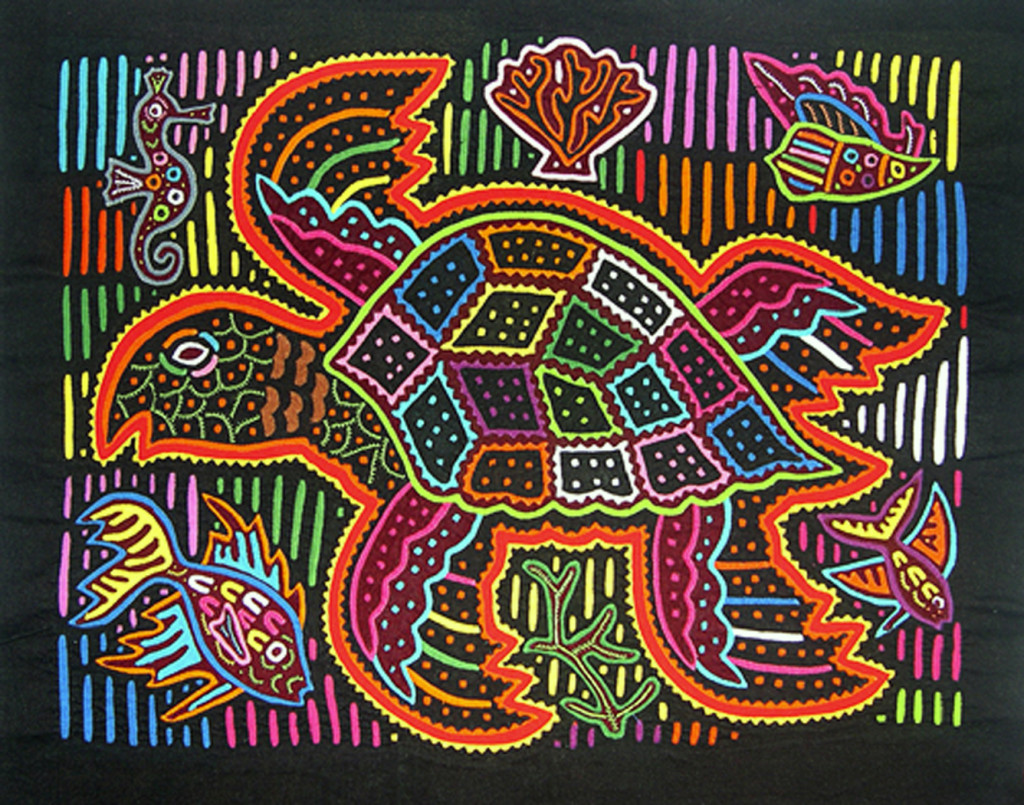

Molas typically use a reverse applique technique, in which fabric is layered and then cut away to create a design. Traditional designs range from complex geometric patterns to depictions of turtles, jungle birds and other things found in the Kunas’ environment. But over time, molas began to include references to the modern world: coins, helicopters, pop culture.

The craft “has evolved with technology and changing times,” said Joan Sasse, who works at the Tucson Museum of Art and included molas in an exhibition on view through June 19 called “La Vida Fantastica: Selections from the Latin American Folk Art Collection.”

The show’s name translates to “the fantastic life,” and Sasse wanted to include molas because she liked “the idea of embellishing an otherwise functional garment to raise it up to the level of something fantastic and visually appealing.”

Kate Mathews, a mola collector and author of “Molas!: Patterns, Techniques, Projects for Colorful Applique,” said the technique involves more than just cutting away material. Mola makers also trim scraps into shapes that are then sewn on top of panels, she said, while other molas use inlay applique, with small bits of fabric sewn between layers, and overlay applique, where the design is rendered with visible stitches on the top layer.

Mathews’ book, various online videos and other resources show how molas can be adapted for DIY projects and kids’ crafts. One simple example: You can layer colored construction paper and cut away shapes — a cat, perhaps, or a diamond pattern — to reveal different colors in different sections of your final picture.

Why are molas so captivating?

“I think it’s the bright colors and the kind of folk-art appeal of simple shapes and interesting interpretations of the world,” said Mathews. “The women get their ideas from the world around them. Molas might show flora and fauna or other types of natural shapes, or they might be manmade objects like a Coca-Cola bottle.”

Joan Jacobson, who gave the Tucson Museum some of the 40 to 50 molas she has collected, said she bought her first molas on a trip to Panama decades ago. The women “were selling them. You’d walk around and see them doing the needlework,” she recalled. “I’ve always been interested in textiles — I’m a weaver.”

She loved the molas’ bright colors and whimsical designs, featuring everything from geometric patterns to airplanes or hot-air balloons.

Anna Bonarou, a contemporary textile artist in Greece, has studied molas for inspiration in her own work, and marvels at the Kuna women’s skill in creating designs with little more than needles and scissors. She used a computer to recreate the complex geometric patterns.

“Although I had studied architecture, it was very difficult to do,” said Bonarou.

She also became interested in Kuna culture. “For me the best way to love something is to learn the story behind the craft,” she said. “The craft is not only the materials and the technique.”

Bonarou has incorporated elements of molas in her abstract wall art, often in black and white rather than the Kunas’ bold colors. The craft, she says, is time-consuming, requiring “a lot of patience, so that your hands, with the needles, start to feel pain.” But it’s “also something to bring you inspiration.”