To many in the United States, the Stevens name means very little, certainly less than it does to those in Panama, where a monument recognizes the man in the canal’s headquarter city of Balboa.

Family archives — pictures from Panama and letters from President Theodore Roosevelt — paint the picture of a man who was intimately involved with the major changes of the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

With little formal training, Scott Hawks said, Stevens became a railroad surveyor and eventually discovered safe railroad passes across the Rocky Mountains in Montana and Cascades in Washington.

It was that success that attracted the attention of Roosevelt, who tapped the self-taught engineer and surveyor to take the lead on the canal project after its first chief engineer quit abruptly.

“He lived in a time when you could really make some waves,” Scott Hawks said. “And he did.”

Building the canal took nearly five decades, 80,000 laborers and leadership from four French and American engineers, including Stevens. It is estimated that 30,000 people died in the process.

As leader of the project, Stevens focused not just on finishing the canal but on caring for workers’ health.

“The other big accomplishment he had was working with Dr. Gorgas to eradicate malaria,” Scott Hawks said.

When it was finished in 1914, the canal represented a transportation revolution and cut in half the journey cargo took from the U.S. East Coast to its increasingly populous West Coast.

Today, about 12,000 vessels cross the canal each year, according to the Panama Canal Authority.

John Hawks remembers the first time he crossed. It was in 1996, on a two-week cruise with his wife.

“It was fantastic,” he said. “They had lectures on the boat about the canal and Stevens. I attended all of them and actually made some comments during the presentations.”

Few in the family have taken the same path as Stevens. John Hawks is a retired banker, and his son went into business, derailing his plans to study engineering at Purdue University.

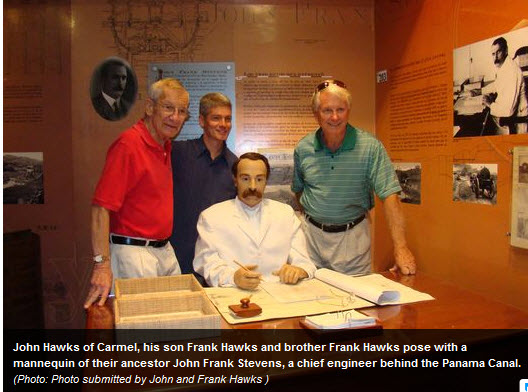

But they keep alive the memory of their illustrious, though sometimes forgotten, ancestor. Both men have the middle name Stevens, and there are numerous Johns and Franks in the family line.

Hanging on the wall in John Hawks’ home is a flag, given to Stevens by Roosevelt himself. It’s a reminder to him of the Stevens family’s contribution to the world.