In an excellent commentary that I read in the Inter American Dialogue, several lead analysis of world political affairs explore why Edward Snowden has been offered asylum in several Latin America Countries.

By William McIlhenny, Daniela Chacón Arias, and Carl Meacham

Latin America Advisor, July 8, 2013

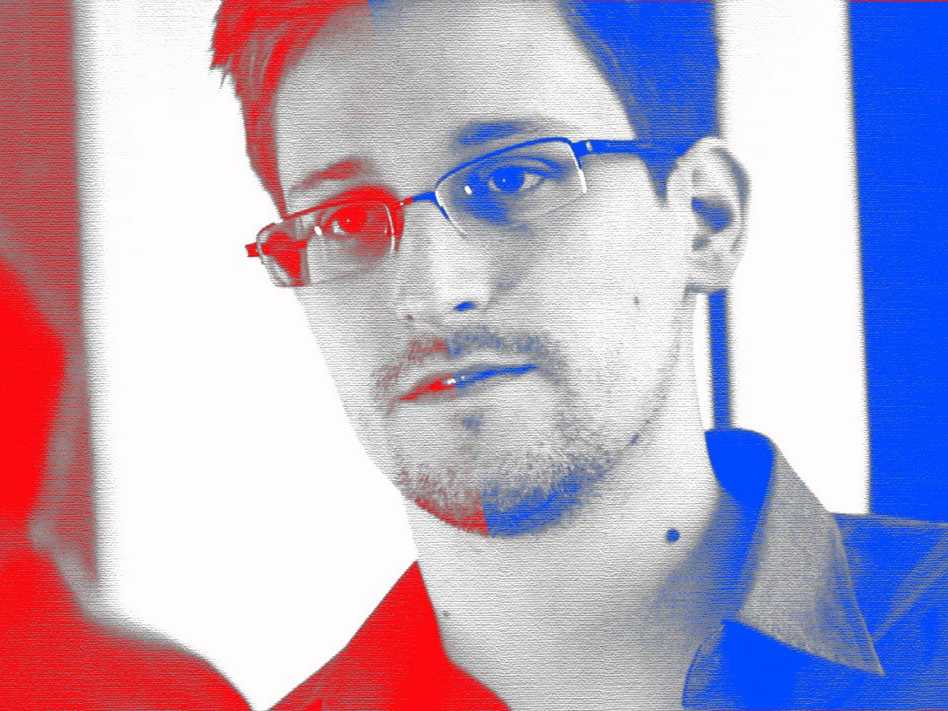

Q: Former National Security Agency contractor Edward Snowden is the latest high-profile fugitive to seek political asylum from the United States in Latin America, where the presidents of Nicaragua, Venezuela, Bolivia and Ecuador last week expressed varying degrees of willingness to offer him asylum. Why are some governments in the region so eager to thumb their noses at the United States? Have U.S. diplomatic efforts failed to create stronger allies in the region? Does the general public in Latin America view the U.S. as negatively today as some of their political leaders?

A: William McIlhenny, policy director of the Annenberg-Dreier Commission on the Greater Pacific and a former advisor at the State Department and National Security Council: “I’d look at this another way. If the 21st century is about anything, it’s about new—and big—opportunity. All over Latin America, responsible leaders, of many political traditions, understand that. More important, so do their peoples, across all sorts of cultural divides. I think the same is obviously true in North America, Europe, Asia, and other parts of the world. Nearly everywhere, governments and societies are trying to figure out how to capitalize on the game-changing opportunities all around us to strengthen growth, development and human opportunity. They are finding new ways to leverage their peoples’ empowerment and open exchanges (e.g. of goods, services, capital, information) to accomplish this. There are a some outliers. These include a few Latin American countries whose populist rulers harken back to a problematic past most of the region has surpassed. It isn’t hard to understand why people who have long felt marginalized (and usually were) are vulnerable to demagogues with simple formulas of blame and personalist redemption. It also isn’t hard to understand why rulers who can’t deliver the goods to their people try to distract their attention. That is where operatic gestures like high-profile asylum offers come in. Maybe in some situations this is good base politics for a day. But, even where this game is shrillest, majorities of the public express favorable views of the U.S. So, I think there is diminishing usefulness in these tactics. If anything, they underscore how out of sync a handful of rulers are with the rest of the world, and even with their own countries’ needs. People aren’t stupid, and they don’t want bread and circuses. They want a better future, with jobs and economic opportunity. They want security and universal rights. They want efficient services, and government transparency. Those are the kinds of standards they will ultimately (and appropriately) hold their governments to account for—not who they give asylum to, or how loudly they can rant against foreign scapegoats.”

A: Daniela Chacón Arias, political analyst at Profitas in Quito: “Ecuador, or any other country, has a right to analyze any asylum petition and decide whether to grant it or not under the rules of international law. This does not mean an eagerness to thumb their noses at the United States, but it is an expression of their own policies and traditions regarding asylum requests. Ecuador, under Correa, has had the policy of confronting the United States on the issues he considers violations of the country’s sovereignty. Confronting the United States has always been popular in Latin America due to the past history the region shares, but that does not mean that there are widespread negative sentiments against the country. As for the Snowden case, unfortunately it was poorly handled by the Ecuadorean government and has created negative commercial effects. Ecuador has renounced the ATPDEA trade preferences, and the United States has declared that the renewal of the GSP preferences are not a given. President Correa, after a call with Vice President Biden, has already declared that the country made several mistakes in this case, and that the asylum request will only be analyzed and consulted with the United States once Snowden steps on Ecuadorean soil. Therefore, it is no longer sure that Ecuador will grant the asylum. Nonetheless, commercial relations with the United States have already suffered, as has the image of Ecuador in the world.”

A: Carl Meacham, director of the Americas Program at the Center for Strategic and International Studies: “It is, in simplest terms, unremarkable for the United States to find that the entirety of Latin America is not united behind us. In every region of the world, the United States’ reputation is vulnerable to a handful of states whose priorities and beliefs overlap little with our own. That said, the Obama administration would be served well to articulate and work toward a compelling vision for the region and its future—though, to be sure, recent rhetoric and the president’s and vice president’s visits to the region earlier this year are steps in the right direction. Taking that still further would require that the United States identify and pursue allies that are willing, capable, compatible, and relevant in today’s world—a set of qualifications that, while inapplicable to Ecuador especially, certainly hold for many of our regional neighbors. While there are leaders in the region that view the United States in a decidedly negative light, the majority of the Latin American public sees things somewhat differently. Having long since moved out of the Cold War perspective, ‘millennial’ generation Latin Americans in particular have adopted a more pragmatic view of their northern neighbor and its place in the world, understanding that U.S. policies—like those of other countries in the region and world—are driven by the country’s self-interest. And, whether because they see U.S. power as waning or because, more than ever before, emerging powers all around the world present

a viable alternative to U.S. influence, Latin Americans look at the United States without illusions. Edward Snowden’s publication of classified NSA documents certainly surprised and angered many Americans. But it is important to remember that the information he disseminated was of high value to those countries around the world on less-than-perfect terms with the United States. The fact that Ecuador and Venezuela have shown willingness to consider harboring Snowden is, given their history with the United States, far from noteworthy—particularly in light of Snowden’s requests for asylum assistance to 21 countries around the world. While Ecuador and Venezuela demonstrated their potential support early on, their willingness to consider Snowden’s request is no different from that of any other country around the world.”