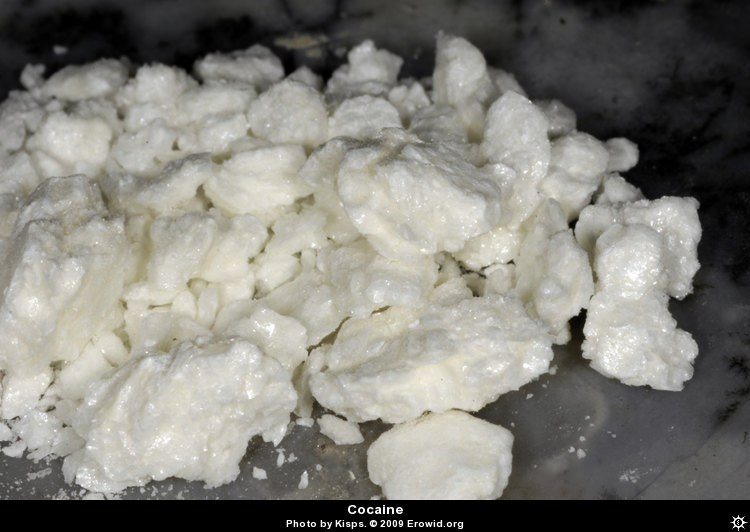

Panama’s Senan aero-naval service said Monday that it confiscated 1,525 kilos (3,359 lbs.) of cocaine during an operation last week off the country’s Caribbean coast.

The drug stash was found in 61 sacks lined with adhesive tape of different colors.

The drugs were dumped in the sea some 16 nautical miles northeast of Tiger Island by the speedboat’s crew, who then managed to get away, Senan said in a communique.

The operation was launched last Friday when Senan units were patrolling the area.

Since 2009, Panamanian authorities have seized more than 99,800 kilos (110 tons) of cocaine, heroin and marijuana, according to data released by Senan.

This year Senan has nabbed approximately 1,725 kilos (3,800 lbs.) of drugs and has destroyed some 4,083 marijuana plants. EFE

Here in a report from Stratfor the leader in Global Intelligence we examine the current routes for drugs moving north. First this map illustrates the traditional air routes leaving South America

Summary

The number of flights carrying cocaine through Honduras, the most common gateway to Central America for U.S.-bound cocaine, appears to have fallen drastically over the past 18 months. Honduran authorities have not reported any seizures of drug-smuggling planes in 2014, and only eight such interdictions were reported in 2013. By comparison, 50 seizures were reported in 2009. During a visit to Honduras in February, U.S. Assistant Secretary of State William Brownfield said the number of suspected smuggling flights detected by the United States had fallen by around 75 percent since 2011, when 100 such aircraft were spotted. Brownfield’s announcement reinforced a Honduran air force claim that drug flights in the third quarter of 2013 fell by 50 percent from the previous year.

However, the apparent decline in aerial smuggling of cocaine does not mean that authorities have stemmed the flow of drugs through Central America. Instead, narcotics traffickers have likely shifted to maritime transport in response to increased attention on drug-laden aircraft by U.S. and Honduran authorities.

Analysis

Cocaine has flowed through Central America to the United States for decades. Over the past five years, an increasing majority of U.S.-bound cocaine from Colombia and Venezuela has entered the region via flights to Honduras. This shift is owed mostly to ineffective law enforcement in Honduras and a low risk of detection compared to Caribbean routes around the Dominican Republic and Puerto Rico, which the United States patrols heavily. Traditionally, the vast majority of cocaine traffic has entered Central America by maritime means such as speedboats, shipping containers or coastal ships. However, the use of aircraft to transport cocaine appeared to increase significantly in 2009, when the U.S. Joint Interagency Task Force detected 54 suspected drug flights into Honduras — up from 31 in 2008. Most of these aircraft departed from remote locations in eastern Colombia and southwestern Venezuela.

The region’s narrow isthmus forms a geographic chokepoint for cocaine flows, and the spike in aerial and maritime smuggling activity in the region attracted the attention of U.S. law enforcement. In April 2012, the United States began an aggressive interception program called Operation Anvil in conjunction with Central American police and military forces. The initiative, which targeted aerial and maritime operations, appears responsible for the decline in drug trafficking flights.

Continued Flow of Cocaine

However, several measurements suggest that this success has not translated into reduced flows of cocaine to the United States. The United Nations and the U.S. Office of National Drug Control Policy suggest that U.S. demand for the drug has either remained stable or has only slightly declined over the past several years. Meanwhile, measurements of cocaine availability in the United States also do not suggest a shortage. If the availability of cocaine dropped relative to demand, purity would drop significantly, too, and retail prices would spike. U.S. estimates show that the purity of cocaine trafficked in bulk has fallen to 70 percent from about 80 percent since 2007 — not a significant enough drop to indicate a supply problem — while retail prices have risen only slightly. Similarly, there have been no definitive signs of a slowdown in coca planting or cocaine production in South America.

Given the lack of noteworthy changes in the cocaine market, the reduction in drug flights to Central America implies two possible changes: Either cocaine trafficking routes have shifted, or the preferred means of smuggling have changed. Most likely, traffickers have adapted to heavier aerial law enforcement pressure in Central America since 2012 by shifting to maritime transport. Aircraft illegally entering the airspace of Central American countries are more likely to attract attention from authorities than marine vessels, which can be more easily disguised as legitimate traffic.

The Shift to Maritime Transport

Cocaine traffickers likely are not abandoning the Central American route, since the region is far too important to Mexican drug trafficking organizations and their northbound smuggling networks. These groups began using this route heavily in the early 1990s, when aerial interdiction and surveillance efforts in parts of the Caribbean near the United States hampered large-scale smuggling through the region. The reliance of Mexican cartels on the Central American route increased after 2006. That year, increased Mexican government pressure made it more difficult to transport South American cocaine directly to Mexico. According to a U.S. government estimate, by 2013, around 80 percent of all cocaine entering the United States was passing through Central America.

A shift to maritime transport in Central America would not be unprecedented. Seven years ago, the Dominican Republic experienced a spike in cocaine-smuggling flights similar to those seen recently in Honduras. The number of suspected smuggling flights detected by the U.S. Joint Interagency Task Force rose from 17 in 2004 to 119 in 2007. Just 13 such flights were detected in 2010, while aerial transport through Honduras apparently increased. However, despite the decline in drug flights through the Dominican Republic, drug smuggling to the island by ship continued unabated. For the past several years, most of the cocaine seizures in the country have occurred offshore.

The reliance on maritime smuggling is evident elsewhere in the cocaine supply chain. Recent seizures suggest that because of the reduction in air transport, more cocaine is passing through ports in Colombia, Venezuela and Ecuador. On March 4, Colombian authorities intercepted 770 kilograms (roughly 1,700 pounds) of cocaine on a boat bound for Central America. On Feb. 5, Colombian police discovered 1,900 kilograms of cocaine headed to Guatemala in a container at the port of Barranquilla. On Jan. 30, Honduran authorities seized 2,000 kilograms of cocaine in a container from the Colombian port city of Buenaventura. Since mid-2012, the Urabenos, one of Colombia’s largest criminal groups, has fought a turf war in and around Buenaventura against a criminal group known as La Empresa. At stake in this conflict is the ability to export cocaine through the port facilities there. Criminal organizations have waged similar, albeit less intense conflicts for control over the lucrative port cities of Barranquilla and Cartagena.

Shifts in cocaine smuggling patterns are never permanent. Traffickers often change smuggling routes and methods in response to changes in interdiction efforts. The recent decline in drug flights will continue only so long as criminal organizations perceive a risk to their ability to transport cocaine through the air. If U.S.-led counternarcotics activities in Central America decline, traffickers could easily resume drug flights. The ebb and flow of counternarcotics efforts is determined primarily by the availability of U.S. assets, such as Drug Enforcement Administration personnel, that are not permanently based in the region. Since local forces are incapable of replacing U.S. resources whenever U.S. attention wanes, drug flights could increase once again in coming years.