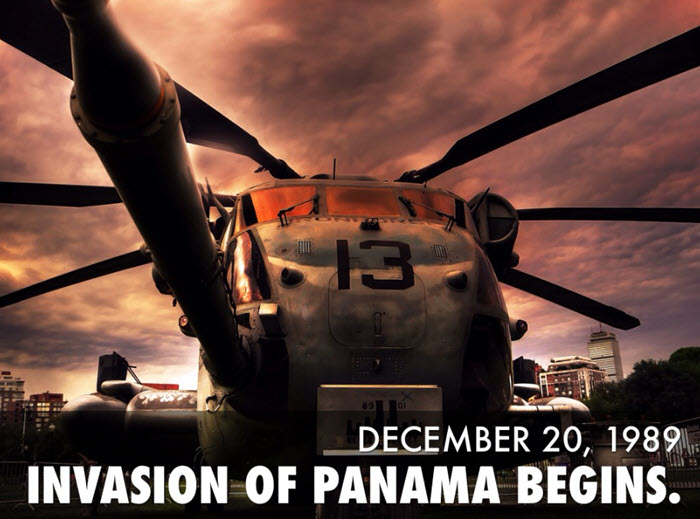

Last year marked the 30 anniversary of the US invasion of Panama. A very controversial subject and a sad time indeed with all that happened just to get one man. I read history for one reason that we all should do and that is to learn from our past mistakes so as not to repeat them.

Many stories surfaced and I found one odd but intriguing.

A rotting cow tongue and ‘evil sorcery’: How the U.S. invasion of Panama led to a literal witch hunt

In 1989, after American troops deposed Gen. Manuel Antonio Noriega, the strongman disappeared, and so did a Brazilian witch he relied on for weird occult rituals.

William Branigin at WAPO writes this story.

James R. Dibble, a special agent with the U.S. Army’s Criminal Investigation Command, pried out the nails and unfolded the tongue. Inside it, a name appeared to be written in ink. The writing was illegible, but judging by other items found in the house inside Panama City’s Fort Amador, the concoction was aimed at casting a spell on a Noriega enemy in a voodoo-like ritual.

So began a strange foray into the dark world of the dictator who had ruled Panama with increasing ruthlessness for the past six years — at least part of that time with the help of a woman identified by the Army as a Brazilian witch, a sorceress skilled in the black magic and occult rituals that Noriega practiced.

Three decades ago, 24,000 U.S. troops invaded Panama, driving Noriega from power and handing the presidency to an opposition leader who had won a May 1989 election in a landslide, only to see Noriega negate it and declare himself “maximum leader.”

His Panama Defense Forces headquarters in ruins, Noriega went to ground, setting off a manhunt by U.S. forces before he slipped into the Vatican Embassy on Christmas Eve in 1989 to request political asylum. The Brazilian sorceress vanished, too, triggering what might accurately be called a witch hunt.

The religious paraphernalia and occult items that Noriega left behind in what soldiers dubbed “the witch house” provided a fascinating glimpse into the psyche of an enigmatic man who had been a CIA asset during his rise to power, yet had also helped rebels in Central and South America and had profited from drug and arms trafficking. Reviled by many Panamanians and mocked with the nickname “Pineapple Face” for his acne-scarred complexion, Noriega wielded power as military commander through figurehead presidents.

U.S. investigators came to believe after his ouster that many of his puzzling actions could be attributed to his occult rituals. But in the end, witchcraft proved no match for the 82nd Airborne and other troops that descended on Panama City in the early hours of Dec. 20, 1989.

The events that led to that point began building the previous year, when Noriega was indicted by two federal grand juries in Florida on drug trafficking, money laundering and racketeering charges and Panamanians stepped up demonstrations against his repressive rule. Noriega, in turn, escalated police and military harassment of Americans living in Panama, who numbered more than 40,000 in the country of 2.2 million people.

To help put down the protests, he formed paramilitary units called Dignity Battalions with help from Cuban advisers. Ostensibly made up of civilian supporters, the Dingbats, as the U.S. military called them, had a hard core of plainclothes members from the Panama Defense Forces. Also active in the suppression business were riot police units called Dobermans and water cannon trucks known as Pitufos (Spanish for Smurfs) for the blue cartoon characters inexplicably painted on their sides.

The unrest came to a head after the May 7, 1989, presidential election, when exit polls and partial returns showed opposition leader Guillermo Endara winning by a 3-to-1 margin over Noriega’s candidate, businessman Carlos Duque. And that was despite what outside election observers, including former president Jimmy Carter, described as extensive fraud.

On the night of May 9, after reporting on the regime’s efforts to stall the vote count and steal thousands of ballots in raids on tallying centers, I was driving to a restaurant in a rental car with three other American correspondents when we were pulled over by two truckloads of Dobermans. Plainclothes agents, apparently from the feared G-2 military intelligence branch that Noriega once headed, quickly arrived on the scene. With me in the car were Phil Bennett, then with the Boston Globe; Ken Freed of the Los Angeles Times; and Chuck Lane, then a correspondent for Newsweek.

After some debate about what to do with us — and apparently thinking that we were U.S. service members and that they had hit some sort of gringo jackpot — the G-2 men decided to split us up and take us to four different locations.

It was at times like this when I had a real problem with authority. Not liking our captors’ plan at all and struggling to keep my temper, I refused to get out of the car. At that point, a particularly thuggish agent hauled me out and handcuffed me to Freed. As we were being taken into custody, a well-known American network correspondent, whom we were supposed to meet for dinner, drove by the scene. Not only did he not stop to offer any assistance, but he apparently didn’t report our arrest to anyone.

What followed was a wild ride through the streets of Panama City, with a G-2 man at the wheel of my rental car, the thug in the passenger seat, and Freed and I handcuffed in the back seat. Arriving at a police station, we were pulled out and marched in.

“Who’s in charge here?” I demanded indignantly. To which an officer imperiously replied, “General Manuel Antonio Noriega.”

But Panama’s finest wanted nothing to do with us, so we were driven off again, this time to a G-2 office near Noriega’s Command Headquarters, known as the Comandancia, in the city’s rundown El Chorrillo neighborhood.

Lane and Bennett were taken to a different police station, where they were held in a room crammed with stacks of cardboard boxes. They soon noticed that the cartons were filled with ballots from the election, and a disturbing thought occurred to them, as Lane, now an editorial writer at The Washington Post, recounted later: How could their captors let them live after seeing this blatant evidence of electoral fraud?

Eventually, however, Lane and Bennett joined us at the G-2 office, and we were all subsequently released with an explanation that it had all been a misunderstanding.

nable to reverse its overwhelming defeat at the polls, the regime the next day annulled the election and dispatched troops, Dobermans and Dignity Battalions to attack a protest motorcade led by Endara and disperse crowds that turned out to cheer him.

Endara and his two vice-presidential running mates, Ricardo Arias Calderón and Guillermo “Billy” Ford, were beaten with clubs and iron bars, and two of their bodyguards were shot, one fatally. Endara was knocked unconscious with a blow to the forehead. Ford, his white guayabera drenched in his dead bodyguard’s blood, tried to fight off a Dignity Battalion attacker before being arrested.

The rotund Endara, his head swathed in a bandage, later went on a hunger strike. He lost about 30 of his 265 pounds, but it was not enough to shed his nickname: Pan Dulce (roughly, Honeybun), after the Mexican pastry.

Indulging in reporters’ gallows humor while driving around the city, we made up a song to the tune of Bobby McFerrin’s hit at the time, “Don’t Worry, Be Happy.” Sample lyric: “Dignity Battalion they stop your car/ Beat your face with an iron bar/ Don’t worry. Be happy.”

In October, Noriega further consolidated control when he put down a coup attempt and, according to U.S. intelligence reports, personally participated in executing its leaders. Disgruntled American officials lamented a lost opportunity, saying the mutiny might have succeeded if U.S. forces in the Canal Zone had intervened.

The regime in mid-December nevertheless declared Panama to be in a “state of war” with the United States and named Noriega “maximum leader for national liberation,” while continuing to harass Americans.

For President George H.W. Bush, the last straw came the next night, when four unarmed American service members were heading to dinner in the city. A wrong turn led them to a checkpoint in front of the Comandancia, where a confrontation ensued. As the Americans tried to drive away, Panamanian forces opened fire on their car, killing a Marine, 1st Lt. Robert Paz.

Bush launched the invasion, dubbed Operation Just Cause, a little more than 72 hours later. U.S. forces besieged Noriega’s Comandancia and quickly rolled up his 16,000-member Panama Defense Forces. But they did nothing to stop an outbreak of looting that followed.

At the time, I was in Ciudad Juárez, Mexico, preparing to cross the U.S. border with my wife and two small children to spend Christmas with family. Instead, I had to leave them there and head back to Panama. But the international airport was closed, so The Post chartered a small plane, which picked me up in Costa Rica, and I flew with a small group of reporters into Howard Air Force Base in the Canal Zone. Also part of our Washington Post invasion crew in Panama were reporters Al Kamen, Dana Priest and Joanne Omang.

Shortly after landing, a couple of other correspondents and I gave our U.S. military minders the slip and took a harrowing car ride through downtown Panama City. It was utter chaos. Looting was rampant, and business owners were shooting looters on sight to protect their stores, sometimes sniping at them from rooftops.

An estimated 300 civilians died during and immediately after the invasion, including those killed in the looting, according to Panama’s Forensic Registry. The U.S. military reported 23 of its troops and 314 enemy combatants killed in the fighting, but Panama’s Institute of Legal Medicine later said only 63 Panamanian military personnel died.

Noriega, meanwhile, had disappeared.

In addition to searching for him, the Army also was looking for evidence of drug trafficking. Which brings us back to Noriega’s two-story house near a U.S. officers’ club at Fort Amador, a military base used jointly by U.S. and Panamanian forces. It was there that soldiers found a freezer full of bundles of banana leaves wrapped around a white powdery substance that they initially declared was cocaine.

It wasn’t. The Army later retracted that announcement and said the soldiers had actually found a stash of tamales. But that wasn’t quite right, either.

Dibble, the Army’s Criminal Investigation Command agent, was called in to help investigate and quickly realized that the “tamales” were part of what he called “evil sorcery,” in this case, “binding rituals” intended to neutralize opponents by symbolically enclosing them in gooey substances.

Indeed, inside the “tamales” were slips of paper with the names of enemies written on them. One particularly smelly one contained the names of former New York Times reporter Seymour Hersh, who had written about Noriega’s involvement in drug and arms smuggling, and Reagan administration national security adviser John Poindexter.

Also recovered was a glutinous ball of cornmeal wrapped in blue ribbon and white string. Dibble opened it to find a picture of Endara crumpled inside. A photo of former president Ronald Reagan was stuck in an ashtray under a layer of red wax.

Papers found with moldy fruit contained the names of President Bush and two U.S. senators, as well as a general reference to “Congress U.S.A.” Also listed: Henry Kissinger, U.S. military and embassy officials, the presidents of Venezuela and Costa Rica, Catholic leaders including the archbishop of Panama, the U.N. secretary general, various Panamanian opposition figures and even close Noriega allies and military officers, suggesting mistrust within his inner circle.

Dibble, an expert on the occult who taught on the subject at a Tennessee university at the time, determined that Noriega practiced different Latin American religions that mixed African tribal beliefs and Roman Catholicism. They included the “benevolent magic” of Santeria and Candomblé, as well as the “evil magic” of brujería, or witchcraft.

That was where the Brazilian witch came in. Judging by a lit cigarette in an ashtray, she apparently fled the house minutes before U.S. troops arrived, leaving behind identity papers, photos and a diary in Portuguese.

She was identified as Rosileide dos Gracias Oliveira, then 27, a plump, dark-skinned woman from Rio de Janeiro whose picture hung on the walls of Noriega’s home and office.

“I knew Noriega was diabolical … and he ruled through fear,” Dibble said this month. But until he walked into the witch house, he said, “I had no idea he was involved in any of this.”

In early January 1990, Noriega abandoned his refuge in the Apostolic Nunciature. He was taken into U.S. custody and flown to Miami, where he was later tried and convicted. He served 17 years in federal detention before being extradited to France, which subsequently sent him back to Panama. He died in custody there in 2017 at age 83.

What happened to Oliveira, the Brazilian sorceress, remains a mystery. Dibble believes she managed to flee Panama and make her way back to Brazil.

And investigators never were able to discern the name on that rotten cow tongue.