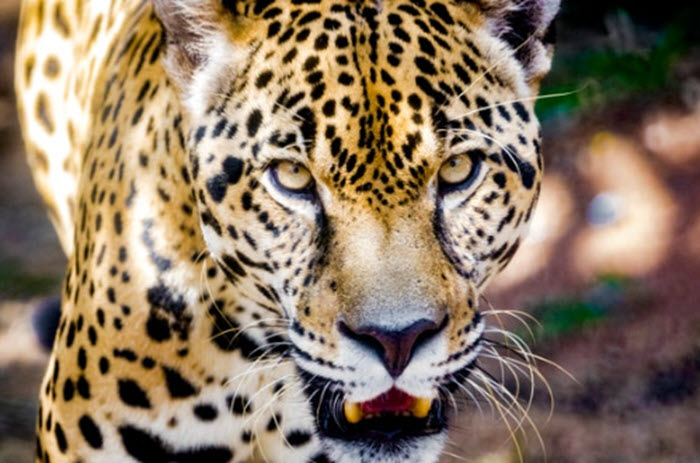

Jaguar is one of the large mammals that are under stress because the Central American wildlife corridor has become fragmented. Credit: Eduardo Estrada, Wildlife and Conservation Photographer.

The expansion of human populations has left animals such as white-lipped peccaries, jaguars, giant anteaters, white-tailed deer and tapirs isolated throughout Panama, a study recently published in Conservation Biology found. The nation represents the narrowest portion of a system of protected areas and connecting corridors that extend through the length of Central America and part of Mexico, known as the Mesoamerican Biological Corridor (MBC).

To assess the health of the corridor, the paper focused on nine species of medium-to-large terrestrial mammals and determined their connectivity—defined as current population distributions in different habitats, movement among habitats and the capability to interbreed. Pumas, red brocket deer, ocelots and collared peccaries, which are more adaptable, were present in more territories, the study determined, but they were also affected by the habitat fragmentation occurring in Panama. “The results strongly suggest that the bridge [through Panama] is broken,” says ecologist Ninon Meyer, who was the lead author of the study and recently received her Ph.D. from the College of the Southern Border in Mexico. “Until a few decades ago, many of these large mammal species still occurred continuously throughout the isthmus”, she says.

Now the animals live in forest “islands,” surrounded by cattle ranches, fields of crops, roads and other human developments that jeopardize their ability to move from one place—and, correspondingly, from one group—to another. “The habitat fragmentation prevents animal movement and gene flow between populations, which can be detrimental to their long-term survival,” Meyer explains.

Panama has always played a crucial role in the movement and gene flow of numerous neotropical forest species. When the Isthmus of Panama, connecting North and South America, emerged about 2.8 million years ago, the event led to the Great American Biotic Interchange, allowing species to migrate between the two continents.

“From an ecological and evolutionary point of view, the Isthmus of Panama is extremely important,” says Alberto Yanosky, a wildlife biologist at Paraguay’s National Council of Science and Technology, who was not involved in the new study. Nevertheless, until now, there was a lack of scientific evidence that highlighted Panama’s key role in maintaining these connected habitats and the country’s impact on the entire MBC—which begins in southeastern Mexico and goes all the way down to Panama’s border with Colombia. The study fills that void, he says, and also proposes a different way of analyzing the concept of connectivity, taking multiple species and their dispersal patterns into account—an approach Yanosky will start to incorporate in his own research and teaching.

“This is the first attempt to estimate how well the narrowest part of the MBC functions as a corridor for large mammals. It comes at an important time, when the results could influence where reforestation to increase carbon storage would also provide connectivity,” says Paul Beier, an expert in the design of wildlife corridors and a professor of conservation biology at Northern Arizona University. “The study suggests that for several species of large mammals, the narrowest part of the MBC—namely, the section in Panama—might not be an effective corridor,” he adds.

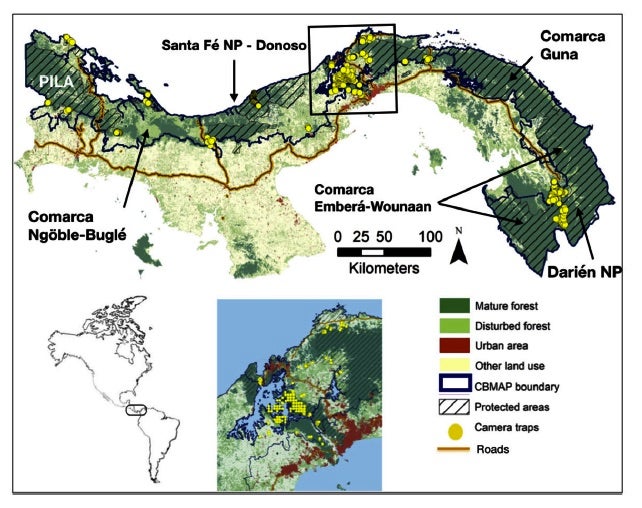

To assess the connectivity of these nine mammal species throughout Panama, 418 camera stations were located in 28 forested areas to record the animals’ presence between 2012 and 2017. “We place the cameras, mainly, on trails and along streams where we know the animals travel,” says Ricardo Moreno, a wildlife biologist at the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute and a co-author of the study. In other places, the cameras were located in a grid, separated by specific distances. “The cameras have sensors that detect heat and movement,” Moreno adds. “Every time an animal passes in front of the camera, it is photographed.” For more than a decade, Moreno, who also leads a foundation called Yaguará Panamá, has been part of a growing group of researchers who have been placing camera traps throughout Panama to study jaguars and other mammals in collaboration with universities and the country’s environmental and agricultural development ministries.

“Camera trapping has really revolutionized the way we monitor wildlife,” says Christopher Sutherland, a statistical ecologist at the University of Massachusetts Amherst and a co-author of the paper. He points out, however, that researchers cannot just rely on images from cameras to say if something is there or not. And that makes statistical models useful: “We use the locations where we do see species to develop an understanding of their detection probability, and that allows us to infer what the probability of the species’ presence at locations where we didn’t detect it,” he says. “We could extrapolate our models, derived from empirical camera-trap data, and estimate the species’ occurrence all across Panama, based on the landscape characteristics of the areas that were not surveyed,” Meyer adds.

The study uses, for the first time, a new metric developed by Sutherland: occupancy-weighted connectivity. It takes into account the species distribution—the probability of a species being found in specific habitats—and the information from the literature about how far animals can travel.

The findings clearly show two areas in Panama still offer a healthy habitat for these species: Darien National Park in the southern part of the country and La Amistad International Park in its northern region. “They are the only areas left in Panama that still have all the species,” Meyer says. “Unfortunately, these two areas are very threatened now. Deforestation and the possibility of the construction of the Pan-American Highway through Darien are a cause of great concern,” she adds.

The two regions reside on opposing sides of the isthmus. Meanwhile the center of Panama is the most degraded region, especially the areas surrounding the Panama Canal basin. The canal itself should be passable to medium-to-large species, given its narrow width and absence of currents. Yet the area is also heavily urbanized. Two highways connect the cities of Colón and Panama, constituting a barrier for wildlife movement. “The results show us where we need to pay more attention. These are the areas where we need to carry out research, conservation and education actions,” Moreno says. The study determined that central Panama has a poor habitat for white-lipped peccaries, giant anteaters and three other species.

“For example, in Barro Colorado Island,” a natural reserve located in the man-made Gatun Lake in the middle of the Panama Canal, “you still have a very small population of tapirs,” Meyer says. “But you see that in all the rest [of the central area], we didn’t capture a single record of tapir, not even tracks. The populations in Barro Colorado Island will just reproduce among each other, and then that will [be reflected in a] lack of fitness [and] hybridization, and they will be more prone to extinctions.”

When habitats are already fragmented, corridors are established to restore connectivity, and they usually have one umbrella species—typically a large carnivore that “is charismatic and attracts more money,” Meyer says. “But what works for one species does not necessarily work for the others. In Panama, we see that the tapirs and the white-lipped peccaries are more prone to a lack of connectivity than the jaguar or the puma.”

The expansion of human populations has left animals such as white-lipped peccaries, jaguars, giant anteaters, white-tailed deer and tapirs isolated throughout Panama, a study recently published in Conservation Biology found. The nation represents the narrowest portion of a system of protected areas and connecting corridors that extend through the length of Central America and part of Mexico, known as the Mesoamerican Biological Corridor (MBC).

To assess the health of the corridor, the paper focused on nine species of medium-to-large terrestrial mammals and determined their connectivity—defined as current population distributions in different habitats, movement among habitats and the capability to interbreed. Pumas, red brocket deer, ocelots and collared peccaries, which are more adaptable, were present in more territories, the study determined, but they were also affected by the habitat fragmentation occurring in Panama. “The results strongly suggest that the bridge [through Panama] is broken,” says ecologist Ninon Meyer, who was the lead author of the study and recently received her Ph.D. from the College of the Southern Border in Mexico. “Until a few decades ago, many of these large mammal species still occurred continuously throughout the isthmus”, she says.

Now the animals live in forest “islands,” surrounded by cattle ranches, fields of crops, roads and other human developments that jeopardize their ability to move from one place—and, correspondingly, from one group—to another. “The habitat fragmentation prevents animal movement and gene flow between populations, which can be detrimental to their long-term survival,” Meyer explains.

Panama has always played a crucial role in the movement and gene flow of numerous neotropical forest species. When the Isthmus of Panama, connecting North and South America, emerged about 2.8 million years ago, the event led to the Great American Biotic Interchange, allowing species to migrate between the two continents.

“From an ecological and evolutionary point of view, the Isthmus of Panama is extremely important,” says Alberto Yanosky, a wildlife biologist at Paraguay’s National Council of Science and Technology, who was not involved in the new study. Nevertheless, until now, there was a lack of scientific evidence that highlighted Panama’s key role in maintaining these connected habitats and the country’s impact on the entire MBC—which begins in southeastern Mexico and goes all the way down to Panama’s border with Colombia. The study fills that void, he says, and also proposes a different way of analyzing the concept of connectivity, taking multiple species and their dispersal patterns into account—an approach Yanosky will start to incorporate in his own research and teaching.

“This is the first attempt to estimate how well the narrowest part of the MBC functions as a corridor for large mammals. It comes at an important time, when the results could influence where reforestation to increase carbon storage would also provide connectivity,” says Paul Beier, an expert in the design of wildlife corridors and a professor of conservation biology at Northern Arizona University. “The study suggests that for several species of large mammals, the narrowest part of the MBC—namely, the section in Panama—might not be an effective corridor,” he adds.

To assess the connectivity of these nine mammal species throughout Panama, 418 camera stations were located in 28 forested areas to record the animals’ presence between 2012 and 2017. “We place the cameras, mainly, on trails and along streams where we know the animals travel,” says Ricardo Moreno, a wildlife biologist at the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute and a co-author of the study. In other places, the cameras were located in a grid, separated by specific distances. “The cameras have sensors that detect heat and movement,” Moreno adds. “Every time an animal passes in front of the camera, it is photographed.” For more than a decade, Moreno, who also leads a foundation called Yaguará Panamá, has been part of a growing group of researchers who have been placing camera traps throughout Panama to study jaguars and other mammals in collaboration with universities and the country’s environmental and agricultural development ministries.

“Camera trapping has really revolutionized the way we monitor wildlife,” says Christopher Sutherland, a statistical ecologist at the University of Massachusetts Amherst and a co-author of the paper. He points out, however, that researchers cannot just rely on images from cameras to say if something is there or not. And that makes statistical models useful: “We use the locations where we do see species to develop an understanding of their detection probability, and that allows us to infer what the probability of the species’ presence at locations where we didn’t detect it,” he says. “We could extrapolate our models, derived from empirical camera-trap data, and estimate the species’ occurrence all across Panama, based on the landscape characteristics of the areas that were not surveyed,” Meyer adds.

The study uses, for the first time, a new metric developed by Sutherland: occupancy-weighted connectivity. It takes into account the species distribution—the probability of a species being found in specific habitats—and the information from the literature about how far animals can travel.

The findings clearly show two areas in Panama still offer a healthy habitat for these species: Darien National Park in the southern part of the country and La Amistad International Park in its northern region. “They are the only areas left in Panama that still have all the species,” Meyer says. “Unfortunately, these two areas are very threatened now. Deforestation and the possibility of the construction of the Pan-American Highway through Darien are a cause of great concern,” she adds.

The two regions reside on opposing sides of the isthmus. Meanwhile the center of Panama is the most degraded region, especially the areas surrounding the Panama Canal basin. The canal itself should be passable to medium-to-large species, given its narrow width and absence of currents. Yet the area is also heavily urbanized. Two highways connect the cities of Colón and Panama, constituting a barrier for wildlife movement. “The results show us where we need to pay more attention. These are the areas where we need to carry out research, conservation and education actions,” Moreno says. The study determined that central Panama has a poor habitat for white-lipped peccaries, giant anteaters and three other species.

“For example, in Barro Colorado Island,” a natural reserve located in the man-made Gatun Lake in the middle of the Panama Canal, “you still have a very small population of tapirs,” Meyer says. “But you see that in all the rest [of the central area], we didn’t capture a single record of tapir, not even tracks. The populations in Barro Colorado Island will just reproduce among each other, and then that will [be reflected in a] lack of fitness [and] hybridization, and they will be more prone to extinctions.”

When habitats are already fragmented, corridors are established to restore connectivity, and they usually have one umbrella species—typically a large carnivore that “is charismatic and attracts more money,” Meyer says. “But what works for one species does not necessarily work for the others. In Panama, we see that the tapirs and the white-lipped peccaries are more prone to a lack of connectivity than the jaguar or the puma.”

Beier relates the resulting impact of that policy: “If we ask for a corridor for one species—say, jaguars—and we get it, but that corridor does not work for deer, or tapirs, or anteaters, we would have squandered an opportunity to conserve biodiversity and ecosystem processes,” he says. “In much of Europe, the eastern U.S., eastern China and parts of West Africa, there are no long-distance corridors,” Beier adds. But all is not lost, because “the opportunity to restore corridors still exists—if we bring back the forests that have recently been lost.”

As for Panama, ecological restoration needs to become more of a priority. “There is still opportunity to restore forest cover in Panama, which could greatly improve the effectiveness of the MBC,” Beier says. “But if current trends of forest loss continue, even species like pumas and red brocket deer—for which Panama is probably a good corridor today—would lose connectivity.”