My friend Sandra Cripe sent me a manuscript of their journey into the Darien Jungle to scratch off another bucket list item in Panama – See a Harpy Eagle, the largest most powerful eagle in the Americas, standing 3 feet tall and up to a 7 foot wing span. It is the strongest bird of prey in the world!! This is a great story and worth reading cover to cover!!

Darien is a challenge to get in and out of and not to be taken lightly as there are many things there that can kill you. Sandra and Lloyd Cripe along with their friends Craig and Sarah made a successful birding trip this last April before the rainy season shuts down access to a large portion of the jungle.

Here is their story:

TO SEE A HARPY EAGLE IN PANAMÁ By Sandra Cripe

Our Darién adventure began Saturday April 6, 2019 at 6:00 am. Our friend and neighbor, Craig Owings, had researched accommodations, made reservations and engaged a private bird guide. His wife, Sarah Terry, my husband Lloyd and I, were in our seats in Craig’s big red Ford truck.

Birding trips are organized like mini-campaigns. The pre-determined start time is always early and there is no tolerance for late sleepers. Be there— on time—with your gear—or—you will—be left behind.

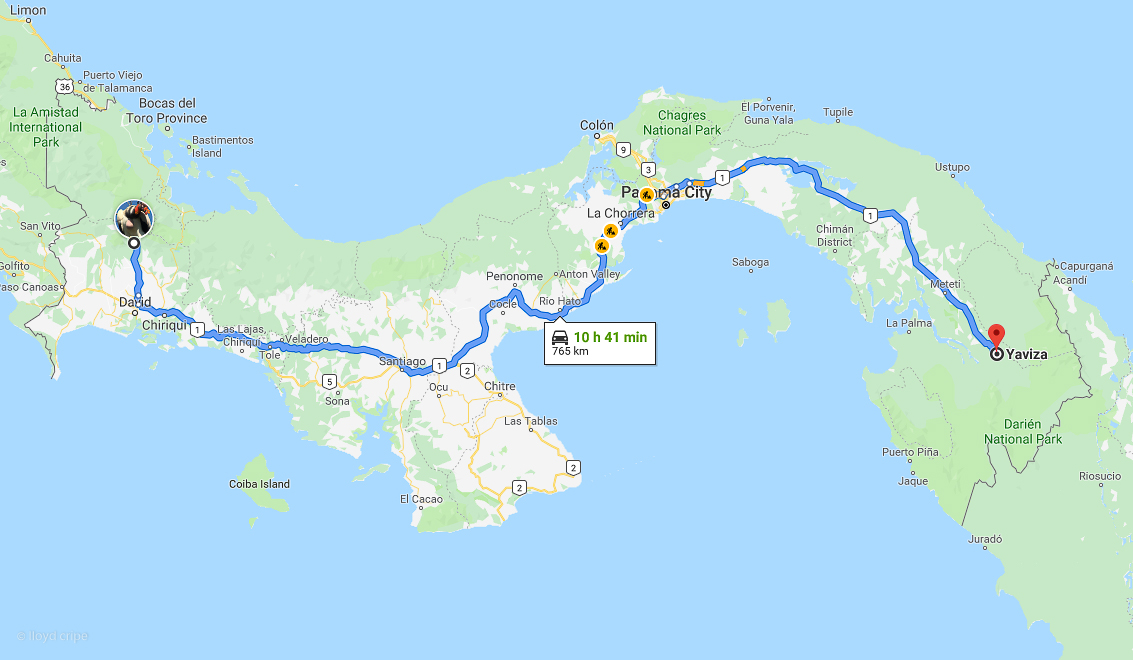

We drove from Palmira, Boquete due east for twelve hours to reach our first destination, Tortí, a town of about 10,000 inhabitants in eastern Panamá province.

See their photo album here with over 200 pictures.

Road-weary, we checked into Hotel Portal Avicar, a hospitable establishment. We met our host, Andres Dominguez. He was, as we say in Spanish, “muy amable,” an expression meaning gracious and friendly.

To access our rooms, we crossed a concrete slab foot bridge and passed by a swimming pool. The rooms were simply furnished but clean and air conditioned. Hot water flowed from the shower, not a cascade but sufficient.

Our group, including friends Ann and Bob Van den Burgh, who drove separately, assembled to eat dinner together. We made our choices from a limited menu and enjoyed a hot meal.

The covered outdoor dining area was designed to delight and entertain birders. Several feet beyond the seating area, the wall of a small building facing the dining table was painted a sky blue and decorated with painted colorful ribbons. Hummingbird feeders hung from the eaves. The feeders were refilled during the day and a variety of hummingbirds visited often. In the fast fading twilight of the tropics, the feeding frenzy reached a fevered pitch. A Black-breasted Mango, looking dapper in his formal feathers, drank and retired to perch near-by. Scaly-breasted Hummingbirds zoomed in, lapped up a quick drink and flew instantly to a nearby branch where they assumed territorial posturing with fully-extended tail-feathers.

Over the past several years, our group has been on birding outings to various areas of Panamá. Who are we? We are retirees, expatriates, “jubilados,” (senior citizens) ranging in age from late sixties to midseventies. Why did we want to make this long trip? Why did we want to subject ourselves to long hot days traveling dirt roads and trekking trails through forests in possibly hostile territory? Why expose ourselves to hungry insects? Why risk failure—not seeing our desired birds? Why subject our aging bodies to the heat and exertion required to survive this excursion?

We are birders. We have birds on our minds and if there are more to be seen, we want to see them. To be a good birder requires attitude, desire for adventures, knowledge, skills, humility and a good pair of binoculars.

We also share deep respect for the awesomeness of Nature. We take pleasure in observing the myriad life-forms that share the Earth with us humans.

My keen-eyed friends, Sarah and Ann, are passionate birders. Lloyd and Craig are bird photographers. Bob is not a birder; however, like all of us, he wanted to see the Harpy Eagle, our target bird.

The Harpy Eagle Harpia harpyja Águila Harpia: in English, Latin and Spanish, is a Neotropical species of eagle found in the canopy layer of lowland rainforests. It ranges from Southern Mexico into South America; always rare, it is becoming endangered due to habitat destruction.

Habitat: the space to survive; to hunt food; to nest; to hatch an egg; to raise a hatchling to eaglet; to nurture the juvenile to independence takes hundreds of acres of forest.

The adult eagles invest between eighteen months to more than two years rearing their young. Once the sub-adult eagle is self-sufficient, it needs an additional large patch of lowland rainforest habitat to begin another lifecycle.

The Harpy Eagle is a raptor, a bird of prey, a “top predator.” It captures monkeys and sloths, and larger birds in its long sharp talons, snatching them from branches high in the canopy and without missing a beat, flying back to its aerie to eat, to feed a brooding mate or the hatchling.

The Harpy Eagle is massive. The females can weigh up to 20 pounds and stand up to 38” in height. The males weigh up to 10 pounds. The leg bones or tarsi have the biggest circumference of any bird of prey. The talons can be as long as a grizzly bear’s claws. The Harpy Eagle has been the National Bird of the Republic of Panamá since April 2002.1

Sunday morning, we birded a section of the Rio Tortí, a short drive from the hotel. It was dry in all of Panamá2 and the river was merely a meandering stream, its water a magnet for living, breathing, drinking creatures. We delighted in seeing “lifers.” For birders, a “lifer” is a first-time sighting of a new species, a trophy to add to our birdlists. Birdlists are a score-keeping method for the game of birding. Lists for the day, area or trip added together become a life list. New entries for my list3 included White-eared Conebill, and Red-throated Caracara, both Darién specialties, meaning they are found only in that area of Panamá; Louisiana Waterthrush; Limpkin; and—Little Cuckoo? Darn, I missed that one!

After lunch and a rest, we again loaded up and drove southeast to the town of Metetí. We spent two nights at Hotel Bellagio. The rooms were large, airconditioned and warm water flowed from the showers. It was also a construction site with equipment, construction materials and debris strewn haphazardly around the parking area. Dust was everywhere.

On the short walk from the hotel lobby door to the restaurant door, we encountered a large wire-caged area holding several colorful tropical birds. They appeared to be healthy and well cared for; however, for birders, seeing incarcerated birds is always a bit sad unless the birds are injured or for some reason need care.

Our hired guide, Michael Castro, met us at meal time and we introduced ourselves. Tomorrow was going to be a long, hot day. Were we up to this challenge? If we were to see a Harpy Eagle in Panamá, now was the time and opportunity. Motivation based on desire is a powerful emotion. Yes, we were ready.

Monday April 8 at 5:00 am: The challenge day begins. We loaded into two vehicles and drove 15 minutes to pick up the young assistant guide, Ismael Quiroz. He is learning the ropes to become a nature guide. He knew the road to the village and protocol for dealing with the tribal people.

Our destination was a specific tree located in the Cémaco Disctrict of the Comarca (reservation) Emberá-Wounaan lands. The tribal people control the land and they know the nest trees. They restrict access to the area and derive income from guiding birders and researchers to active nests. They protect the birds from hunters and set perimeters for intruders like us. No one is allowed to harass the birds by moving too close to The Tree.

We drove about 20 minutes west on Highway One and made a right turn onto an unimproved dirt and gravel road passable only in dry season. The big red Ford truck jounced us along for over an hour before reaching Sinaí, the Emberá-Wounaan village. We parked, collected ourselves and our gear and walked through the village to the port on Rio Chucunaque.

We were sorted into two dugouts called cayugas equipped with outboard motors. Each dugout required two people to operate the craft, a motor person and a pole person. Our pole person was a woman named Elidia. Ahmet was the motor operator.

We were forty-five minutes traveling upriver. The dugouts were surprisingly stable. It was pleasant to ride on the water in the fresh morning air. Weak sunlight filtered through the trees. Birds lined the river banks: A Crane Hawk, with its long beautiful orange legs and deep bluish feathers; a Great Potoo, in full view, sleeping on a branch over-hanging the river; and a Green Heron perched on a slender limb.

Navigation was tricky. To avoid sandbars, the navigators watched for flowing channels. Elidia, and her pole kept us in moving water most of the time. However, even with her powerful shoulders in action, there were times when she could not manage to aim the dugout into the channel between sandbars. When the dugout ran aground, she slid into the water to dislodge and redirect it. At times, Ahmet slid into the water to help her free the craft.

We reached the beachhead to the trail to The Tree to the nest to the Harpy Eagle. It was mid-morning, the early freshness of the day dissipated by the Sun.

I had brought my Nordic walking poles to aid in trekking the trail. Despite coping with low-back, hip and sciatic pain for the past several years, I was determined to walk the trail. I accepted a helping-hand up the river bank but the trail was cleared and passable. It was an hour’s walk for the others and a bit more for me, then there it was—The Tree! I asked Lloyd to take my photo. I positioned the walking poles in a “V” for victory! I made it!

The birds were not in residence when we arrived. We snacked and drank water. Lloyd and Craig set-up their Digi-scopes and trained them on the nest. Some found places to sit on low horizontal limbs and some sat on the ground beneath trees to settle in as comfortably as possible—to wait. We did not know for how long or even if “the object of our desire” would show up. Deep hope radiated from all of us.

Some time passed when suddenly a ripple of energy like an electric current roused the group. There were whispers and hand signals, someone pointed to a branch to the right of the nest—there—a juvenile Harpy Eagle! Oh, Joy! The Reward!

Attention focused, my eyes drank in its details, positions and feathering. I saw it turn its magnificent head and train its eyes on us. It raised and lowered its crest—marvelous!

It was midday and I realized I was running low on energy. Earlier, as we approached The Tree, Ahmet had pointed out a crude pole bench. I went there to rest. What an experience, to lie on my back looking at the sky though leaves and branches of trees in the Darién, the eastern most land of Panamá bordering Columbia, a land of mystery with a historic reputation as a dangerous place to travel.4 The geography, jungle, insects, heat and humidity are all inhospitable. So far, I was coping with two of these challenges: 1) pesky insects, an insect repellent wipe discouraged those, and, 2) heat. No escaping the heat. However, because it was dry season, the humidity was low.

A Blue Morpho butterfly appeared above me and continued on, its iridescent blue wings beating a zig-zag pattern through the forest. After a while, I felt refreshed and decided the better part of wisdom was for me to return to the river rather than wait with the group hoping the adult eagles would show up. I rejoined the group to let them know that I was leaving. I took one last look at the eaglet. It appeared especially young and vulnerable. It had a quizzical (What’s going on?) look on its face. A fringe of stringy white feathers flowed around its huge yellow legs. I wanted to stay longer and observe more of its behaviors, but I had seen it—one more species for my life list.

I requested of Michael that he send a man with me. He sent Ismael, a good choice. He was a congenial companion, pointing out a couple of Coatimundi, a snake skin shed by its owner and a Plumbeous Hawk sitting atop a tree on the horizon. Three times, I needed to stop, close my eyes and breathe, due to the exertion. Every zephyr that ruffled the leaves, every dappled patch of shade was a welcome respite from the brutal heat—near 100 degrees and unrelenting.

Ismael and I reached the river bank where the villagers who had not accompanied us to The Tree were waiting with the dugouts. Soon, the main group arrived. Alas, the adult eagles had not returned to the nest.

We began the downriver return trip. The navigators competently negotiated the uneven water and in a short while we neared port. The scene before us revealed a community at play and work: a man carving a new dugout; twenty or more smiling children splashing in the water; a woman washing clothes using a rock as her scrub board and a stump to hold a basket; farmers parking pickup truck loads of produce at the water’s edge to be transported to market by cayuga; and, young men standing about in waist deep water.

The dugouts were eased onto the beach that served as a port. Mindful of our balance and foot placement, we disembarked.

Our working companions lined up to receive our thanks and gratuities. I specifically asked for Elidia to come forward. She accepted my praise for her hard work and the gift handed to her and a beautiful smile lit up her face. Ahmet received his gift with reserved poise and dignity.

We trudged on to the vehicles. Craig drove the big red Ford truck down the rough dirt road toward Metetí.

We did it! We met our challenge to see a Harpy Eagle in Panamá.5

References:

1 “Law 18 of 2002 made the harpy eagle (Harpia harpyja) the national bird; and to specify what species of eagle was to be on the coat of arms, on May 17, 2006, law 50 was approved by the national Assembly to modify law 18 of 2002, and add that the harpy eagle (Harpia harpyja) was the species of eagle that appears on the coat of arms of the Republic of Panama” https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Coat_of_arms_of_Panama

2 What Panama’s Worst Drought Means for Its Canal’s Future https://nyti.ms/2JrZHwY

3 My birdlist for the April 6-11, 2019, Darién trip: 125 species including 28 “lifers.”

4 PENITAS, Panama (AP) — Panama sees surge in migrants crossing perilous Darien Gap. Read the full story on https://apnews.com/2ac91220638f4318872a6afab1b0315b

5 Lloyd Cripe Photos: Darien Harpy Adventure and Darien Birding Adventure

EDITOR – PS: As I am a proud Panamanian Citizen I decided that my first tattoo would be a Harpy Eagle over the Flag of Panama.