Evan Ellis discusses his take on our relationship with China in this very extensive article

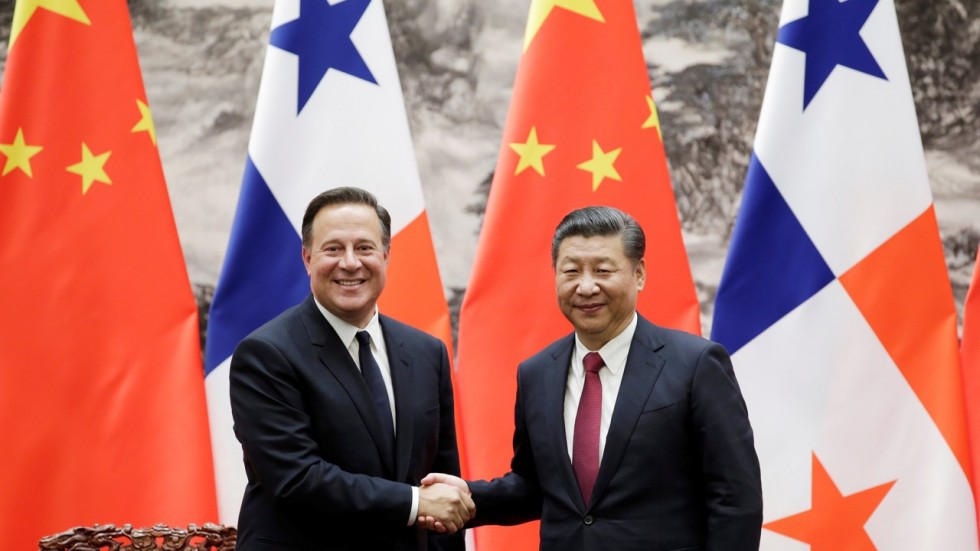

From September 4-14, 2018, I had the opportunity to be in Panama to speak with academics, businesspeople and others regarding the development of the country’s relationship with the People’s Republic of China (PRC) in the 16 months since the two nations established diplomatic relations. My visit coincided with the high-profile dispute over China’s insistence in locating its new embassy on a multi-acre parcel of land on the Amador peninsula and Panamanian President Varela’s reaction implying that a meeting in Washington of U.S. diplomatic personnel to discuss the advance of the PRC in the region put into question U.S. respect for Panama’s sovereignty.

The Panama Canal is central to the politics of Panama, as well as its economic vitality, and the voluntary turn-over of the canal by the United States on December 1, 1999, per the 1977 Torrijos-Carter treaties, was a fundamental milestone for Panama as a sovereign nation. For many Panamanians, the prospect of the PRC flag flying over the Pacific entrance to the canal symbolizes concerns over the de facto erosion of that sovereignty as the Panamanian government of Juan Carlos Varela has signed a series of agreements with the Chinese government. At the same time, PRC-based firms have won a series of questionable concessions in Panama’s logistics, electricity, and construction sectors.

My time and discussions in Panama convinced me that China’s advances in Panama pose strategic risks to both the effective sovereignty of the country, and to the U.S. position in the region.

Although there has been much discussion of the PRC’s use of its new diplomatic relationships in Central America and the Caribbean to establish naval bases or conduct other military activities, the principal near-term risk posed by China through its expanding relationship in Panama is that it will exploit the economic-oriented competition between the country’s family groups—in combination with the malleability of Panama’s political, government, and juridical institutions—to establish itself as a dominant player in key sectors of the Panamanian economy and government. Through that position, many fear, the PRC will further advance its economic and other strategic interests throughout the region.

While I was in Panama, I had the opportunity to meet with a number of current and former Panamanian government officials. I also spoke to China’s ambassador to Panama, Wei Qiang, who impressed me as one of the most capable diplomats that the government of President Xi Jinping has assigned to the region; he spoke impeccable Spanish, had an aura of self-confidence, and apparently has a first-rate tailor. Indeed, in a show of his boldness and initiative while I was in the country, Ambassador Wei caused a public stir when he suggested through a tweet that any U.S. questioning of Panama’s recognition of the PRC was the “purest form of arrogance.”

In the context of such friendly conversations, I do not begrudge either my Panamanian colleagues or my Chinese counterparts in their pursuit of political and commercial advantage. Nevertheless, I left Panama worried that I was witnessing a slowly unfolding major conflict that will not end well, either for Panama’s economic development or for the health and autonomy of the country’s democratic institutions.

China’s strategic envelopment of Panama

From the beginning, a key source of vulnerability for the Panamanian government of Juan Carlos Varela in its dealings with the PRC has been the secrecy with which it has managed the relationship. It has hidden the details of its negotiations and dealings from not only Panamanian government institutions and Panamanian society more broadly, but also from close allies such as the United States. Indeed, President Varela concealed his decision to recognize the PRC from the United States until less than an hour before his public announcement of the change. While doing so was within Panama’s rights as a sovereign country, it was arguably not consistent with its relationship of trust with the U.S. as a friend and commercial partner.

Beyond his lack of consideration with respect to the U.S., in my assessment, President Varela has arguably undercut Panama’s pursuit of its own sovereign interests through managing the majority of his government’s agreements and negotiations with the Chinese out of the office of the Presidency. In the process, his government has excluded itself from the technical support and institutional perspective of other ministries, contributing to the sense of unease within country. Chinese companies have been awarded contracts under questionable circumstances in sectors from ports and electricity generation to a variety of construction projects.

Not only has such secrecy fueled speculation and concern within Panama about what has actually been agreed to, it has created a situation in which China (which has reportedly had surprising access to a broad range of Panamanian government officials and their organizations) may have gained significant insight into the detailed situation and vulnerabilities of Panama’s ministries and commercial partners.

Compounding such concern, the “strategic envelopment” of the Varela government and the intertwined interests of Panama’s family groups are occurring precisely at the moment that the country seeks to conclude a free trade agreement with the PRC, with the third round of those negotiations concluding shortly before the visit of Chinese President Xi Jinping during the first week of December 2018.

Chinese projects which defy economic rationale

On initial examination, the PRC’s growing engagement with Panama is manifested in an array of projects that defy economic rationale. China Railway Group is quietly conducting studies for the construction of a $5.5 billion train from Panama City to David, apparently to be paid for by the Panamanian

government and built by Chinese companies. While a potentially compelling symbolic achievement for President Varela’s embattled Panameñista Party, its cost would rival that of the third set of locks on the Panama Canal. The project doesn’t make clear economic sense given the paltry size of the country’s export-oriented agriculture sector; improvements to local ports and road infrastructure would be far more cost effective than a fast train connection to the capital.

Beyond the train, the Varela government is also paying the construction firm China Harbor to build a port for cruise ships on the Amador peninsula, on the Pacific side of the canal. Not a single person among the numerous maritime industry experts I spoke to in Panama understood the economic rationale of the project, given that there are no significant cruise ship destinations on the Pacific side of the continent to justify the government’s investment to position Panama as a Port of Call.

Suspicious outcomes in public contracts

These China-funded, China-worked mystery projects are complemented by suspicious awards in a series of public contracts involving Chinese companies in Panama. China Harbor, for example, was awarded a contract to construct the fourth bridge over the Panama Canal following the unexplained withdrawal of one of the competitors from the bidding process, despite the fact that China Harbor submitted a deficient design which had to be revised in a manner that resembled that of the competitor who lost the bid.

In the electricity sector, a Chinese company who was disqualified from the bid to construct a fourth power transmission line across the country, was inexplicably re-qualified following an appeal of the decision. The decision raises questions given that one of the agreements signed between the Varela government and the PRC involves PRC financing through the Bank of China for Panama’s public electricity utility company, ETESA.

In a similar fashion, one of China’s petroleum companies may enter Panama’s fuel bunkering sector, acquiring or constructing an offshore facility on the Pacific side of the Panama Canal. The move is likely associated with a petroleum agreement reportedly signed between President Varela’s governments and his Chinese counterparts while the Panamanian president was in Beijing. While modest, such an operation could expand significantly if the Chinese shipping company COSCO increases its use of the Canal and associated ports, as discussed later in this article.

At the Atlantic exit of the Panama Canal, the Chinese group Shanghai Gorgeous is investing $900 million to build a second, 441 MW natural gas fired electricity generation facility, to be completed by 2020. The facility, called Martano, is being built by the Chinese State-owned electric company, Shanghai Electric, and will also store natural gas. The license for the facility, currently held by the NG group, was originally obtained by a Panamanian mall owner and business tycoon in an irregular auction in which there were no competitors. The license was later cancelled and then returned based on an appeal to Panama’s supreme court that was won on a technicality.

Pursuant to China’s granting of “most favored nation” status for Panama-flagged ships accessing Chinese ports (reducing the fees paid by those ships), Panama’s government selected a small Chinese company, New United International Maritime Services, to certify those vessels and their crews. The certification process ran into problems, however, because the Chinese company was not part of the International Association of Recognized Organizations (IARO), the peer group used to establish credibility of certifying organizations.

Other Chinese projects

Even where awards won by Chinese companies and investment deals going forward seem legitimate, the quantity of such outcomes, and their growth in the 16 months since Panama recognized the PRC, is striking.

In telecommunications, the Chinese firm Huawei has an important presence in Panama, including making the Colon Free Trade Zone a regional hub for the distribution of its electronic systems. Huawei has also committed to assemble products there, arguably the most important new investment in the zone as it struggles with the loss of demand in the context of a falloff in business from its two major customers, Venezuela (currently in full economic collapse) and Colombia (in the middle of a commercial feud with Panama).

Huawei’s rival ZTE has a smaller but important presence in Panama. Other Chinese companies have expressed an interest to the Panamanian government in establishing themselves as telecommunications providers in Panama. While to date they have been turned down, a Chinese company could still enter the market in the near to mid-term by acquiring the Panamanian operations of Digicel.

In the crime-ridden city of Colon and the associated Colon Free Trade Zone, Huawei is seeking to install a system of security cameras (possibly including facial recognition capabilities and linked databases). Such a system, if it contained unauthorized “back doors” for diverting the feeds and associated data, could give PRC-based companies such as Huawei unparalleled access to the multitude of licit and illicit operations occurring in the Zone, including the commercial activities of both friends and competitors.

On the Amador causeway—in addition to the Chinese embassy and the inexplicable construction of a cruise ship terminal—the Chinese firms China Harbor, China Construction America, and China Construction Group are completing a massive convention center, begun during the previous administration of Ricardo Martinelli by a contractor who took the pre-payment but did not complete the project.

In the banking sector, the PRC-based Bank of China has had a presence in the country for decades, principally financing purchases of Chinese products through the Colon Free Zone, but more recently serving as the commercial bank for other Chinese companies doing business in the country.

The more commercially-oriented China Construction Bank (CCB) and Industrial and Commercial Bank of China (ICBC) have also taken actions that indicate a possible interest in establishing operations in Panama in the future.

In agriculture, at least 20 groups of Chinese investors have reportedly traveled to the remote rural province of Chiriquí, among other places, to make inquiries regarding projects, including the possible purchase of land, technically not prohibited under Panamanian law.

In the mining sector, Chinese companies have quietly approached small-scale mine operators as potential partners and suppliers. While the country’s highest-profile mine, Mineria Panama, does not officially include Chinese participation, it was the subject of a scandal in which hundreds of suitcase-toting Chinese nationals (apparently mine workers) were documented on the remote mine property.

As suggested by the incident with Chinese at Minera Panama, perhaps one of the most surprising and inexplicable dynamics of China’s advance has been the relative silence of Panama’s normally outspoken labor federations before the Chinese advance. Key labor leaders such as SUNTRACS construction union official Genaro Lopez have reportedly been included in Panamanian government delegations traveling to the PRC. Leaders from the Confederation of Panamanian Workers (CTRP) even signed an agreement with their Chinese counterparts while in China.

While a cause-effect relationship can be proven, the nature of negotiations by Panama’s labor union leaders with the Chinese raise issues in the face of the relative silence of those unions regarding the apparent use of large numbers of Chinese workers on construction projects being undertaken in Panama; the campuses that have visibly been built to house hundreds of Chinese workers in the new Panama-Colon Container Port (PCCP) facility, and at the previously mentioned Amador peninsula cruise ship terminal construction site, have scarcely received mention by the unions.

China’s play in the logistics sector

Even with such a broad range of projects and contracts, the most significant PRC advances in Panama from the perspective of the country, the United States, and the region are occurring in maritime logistics, where China has demonstrated an interest in dominating Panama’s ports and associated logistics services.

Security analysts have arguably misdiagnosed the threat presented by the PRC through their attention to the concession granted to the Hong Kong-based firm Hutchison-Whampoa in 1999 to operate the ports of Balboa and Cristóbal on the Pacific and Atlantic sides of the canal, respectively. While in recent years, mainland Chinese investors have indeed expanded their participation in Hutchison, the strategic challenge that it represents in Panama must be considered in conjunction with the advances of Chinese State-Owned Enterprise China Overseas Shipping (COSCO), recently merged with China Shipping, allied investment groups such as Landbridge and Gorgeous, and allied Chinese construction companies such as China Communications Construction Corporation (CCCC), the parent company of China Harbour.

On the Atlantic side of the Panama Canal, conditions are ripe for COSCO to establish a dominant presence. There, the previously mentioned Chinese investment groups Landbridge and Gorgeous have combined to secure concessions for a major new port operation, PCCP, being built by the construction company China Harbour, and complemented (as previously noted) by a new natural-gas fired power plant and a possible associated facility for storing liquid natural gas for maritime transports and powering port operations.

The construction of PCCP presents a particular challenge for established port operators on the Atlantic side of the canal—Manzanillo International Terminal (MIT), Panama Ports (Hutchison), and Evergreen (Taiwanese). These established operators are already struggling with overcapacity in the context of slow demand growth from Venezuela and Colombia, and with competition from the Colombian port of Cartagena, with its large, efficient consolidation area and base labor costs approximately one-third those of Panama.

While the user of the new PCCP port has not been announced, maritime analysts that I spoke with believe that COSCO is likely to be a key customer. Indeed, COSCO could use PCCP as a strategic vehicle for pursuing its known desire of significantly expanding its own shipping operations in the region, leveraging the PRC’s designation of Panama as part of the “One Belt One Road” (OBOR) initiative.

Adding to concerns, analysts believe that the Taiwanese-owned Evergreen port may be ripe for purchase, possibly by COSCO. Indeed, the appointment of a President at the port with a background in mergers and acquisitions could be an indication that Evergreen may be preparing the operation for sale. A merged COSCO-run port facility combining the PCCP and Evergreen properties (which are physically adjacent to each other), would make particular sense to significantly increase their berths and container handling capacity, particularly since redistribution of cargo to smaller ports is the primary business of most Ports on the Atlantic side of Panama, and the rest of the continent..

A new, combined port could leverage COSCO’s deep pockets to engage in a price war that could drive some competing ports out of business, and possibly induce the Chinese Hutchison port across the canal to cooperate to achieve a coordinated Chinese operation that would effectively re-shape the shipping market in the Atlantic. Indeed Hutchison is already arguably vulnerable to influence from its fellow Chinese shipping and port companies, since its 20-year lease for the ports of Cristobal and Balboa are up for negotiation next year.

On the Pacific side of the canal, Hutchinson’s Balboa port operation is the dominant player. Its position is strengthened by the connection by rail with its port on the Atlantic side (currently owned by Kansas City Railroad, but which the Chinese have already expressed an interest in purchasing).

Building on the dominant Hutchison position in the Pacific, PRC-based investors have reportedly expressed interest to the Panamanian government in leasing a 1,200-hectare parcel of land on the Western side of the canal for use as a logistics park.

While the Panama Canal Authority has ambitions to establish an independent Roll-On-Roll-Off cargo port, and a new container port on the Pacific side (Corozal) in the next two years, analysts consulted for this study believe that an array of 28 legal complaints (which may be encouraged by those with whom Corozal would compete on the Pacific side), will continue to prevent the Panama Canal Authority from successfully establishing the new port.

While Hutchison does also have some competition from the Singaporean Port Authority (PSA) facility on the western bank of the Pacific entrance to the canal, potential expansion of the PSA port as a competitor to Hutchison is limited by a lack of connectivity to the Atlantic by rail, and to the Panama City side of the canal. In addition, Hutchison could have the option to collaborate with other Chinese companies in a massive new logistics park on the Western bank of the canal. Chinese interests could complement the previously indicated dominance of the Atlantic side of the canal, with an expanded dominance of the Pacific side.

The practical effect of Chinese potential future dominance of Panama’s Atlantic and Pacific ports (even though the US is, at present, the top user of the Panama Canal), and the expanded position of COSCO as a major user of the canal, in enabling PRC use of Panama to control regional shipping could further be compounded by the previously unthinkable prospect of a politicized Panama Canal Authority (ACP). Although the organization has long been considered a bastion of apolitical, competent governance, its well-respected director, Jorge Quijano, who led ACP for 7 years and was part of it for over 40, is scheduled to retire this year along with his entire seven-member board of advisors. The risk is accentuated by the fact that three of the members of the executive board who will appoint the next ACP head, including Henry Mizrachi, Nicolas Corcione and Lourdes Castillo, are accused of graft and other serious crimes, and thus susceptible to influence in their voting.

Compounding these vulnerabilities, ACP itself is in the process of reorganization in a way that could strengthen the compartmentalization between its operations and new business organizations, decreasing the ability of experienced longstanding members to restrain its re-orientation in a more politicized direction.

As an indication of such politicization, a Chinese offer to perform a study regarding a fourth, larger set of locks to meet the future needs of the Panama Canal, which was turned down by the Panama Canal Authority four years ago because it had already conducted an analysis, is reportedly once again under discussion.

With such dominance in Panama’s shipping and logistics sector, Chinese shipping companies, operating out of Chinese-run Panamanian ports and backed by Chinese banks with deep pockets, could turn Panama’s declared position on China’s “One Belt One Road” initiative into a powerful tool for driving competing shipping services and port operators out of business. These companies are increasingly in a position to pressure companies and even governments across the region, whose viability depends on imports and exports through such shipping services.

What to do

While the United States has a considerable stake in the outcome of China’s advancing position in Panama, it must manage the challenge with prudence and respect for Panama’s sovereignty.

At the center of its response, the U.S. must strongly encourage Panama to adhere to transparent, objective procedures and the rule of law in dealing with Chinese and other companies. At the same time, it should encourage the country to adhere to its own painstakingly developed plans to advance Panama’s development, such as the National Logistics Plan 2030, rather than allowing Chinese suitors to drive the initiatives that the Panamanian government funds and authorizes in an ad hoc fashion that advances Chinese interests more than those of the country.

The U.S. should not seek to “block” legitimate Chinese commercial activities in Panama or elsewhere in the region. This would only fuel resentment and expand the attractiveness of the PRC to governments in the region as an alternative to U.S. “hegemony.” This does not, however, mean that the U.S. government cannot use its own economic and political influence to seek to counter the PRC, move by move, in its strategic commercial war for geostrategic and economic advantage, where consistent with law and propriety.

As with elsewhere in the region, the U.S. should work with Panama to strengthen governance and fight corruption, including not hesitating to take appropriate action and call attention when it believes that corruption has been a factor in important public contracts and other activities.

When, despite U.S. vigilance and work with Panama against corrupt and non-transparent practices, commercial or government actors in Panama go down a path that is not in keeping with international norms, the U.S. should not hesitate to take appropriate actions to nudge the country in the right direction to preserve the health of its own democratic institutions. Where improper steps are taken by Panamanian government authorities, for example, this could include restricting access to Panamanian-flagged vessels, or from Panamanian ports, to U.S. ports where appropriate standards have not been met in the operation of those ports, and restricting access by Panamanian institutions and individuals to U.S. markets and financial institutions where it appears they have not complied with appropriate norms regarding the certification of their vessels, transparency in the management of their ports, adequate cooperation of port authorities with international law enforcement offcials, or other matters.

In cases where Panama’s actions do not violate international laws or norms, but clearly go against U.S. interests and the spirit of friendship, the U.S should also be ready to apply its considerable commercial and diplomatic leverage to protect those interests. Such actions could include working with international shipping companies and financial entities that depend on U.S. markets to encourage them to lobby Panama to change its behavior.

In the extreme, if a future Panamanian government shows signs of falling strongly under the influence of the Chinese state and its companies, the U.S. may wish to expand its commercial work with partners who better adhere to international norms, such as encouraging the use of Colombian ports for transshipment to U.S. facilities, if the Colombian government demonstrates greater commitment than Panama to transparency and the rule of law.

With respect to the PRC, while the U.S. should not be overtly provocative, it should not be afraid to tell the PRC, in a respectful but firm manner, when it is violating core U.S. interests or international norms. Although the currently unfolding “trade war” between the PRC and U.S. has the potential to cause significant damage for both sides and for the global economy, U.S. policymakers should consider that, under some conditions, the dispute, and subsequent polarization, may be a preferable outcome than continuing acquiescence to aggressive Chinese behavior, including systematic theft of intellectual property and other predatory trade practices.

While the principal risk of the Chinese advance is arguably not military, it nonetheless carries great economic, political and diplomatic importance for the future of Panama, the United States, and the region. China’s gambit may be principally economic, rather than military, but it is worth recalling that the PRC is the only country on the United Nations Security Council not to have signed the treaty committing to the neutrality of the canal.

As I concluded my visit to Panama, a news story reminded me of the Sri Lankan government’s December 2017 handover of a key port to the Chinese after it incurred unsupportable debt for PRC-funded projects. As I followed from Panama the reporting of Venezuelan president Nicolas Maduro’s announcement that the PRC had committed to give his collapsing regime additional funds, possibly in exchange for expanded stakes in Venezuela’s oil fields. Such events made me reflect on the future of Panama and the region. It is in the U.S. interest to work respectfully with Panama to ensure that the Canal and the other attributes which have made Panama a global logistics, financial, and commercial center, continues to benefit a free, democratic Panamanian people, rather than serving as an instrument for an extra-hemispheric power to build its commercial and strategic position in the Western Hemisphere.

Evan Ellis is Latin America research professor with the U.S. Army War College Strategic Studies Institute. The views expressed herein are strictly his own. The author would like to thank Glen Champion, Carlos Gonzalez de la Lastra, Carlos Gonzalez Ramirez, Walter Luchsinger, Jr., Berta Thayer, Tony Bonilla, and Pedro Armada, among others, for their time and insights contributing to this work.