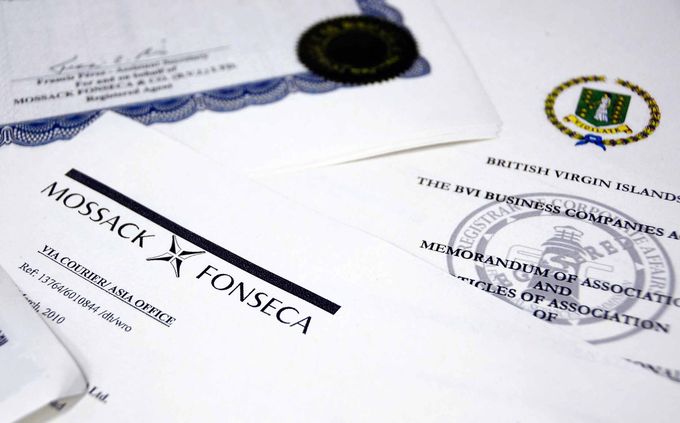

Mossack Fonseca’s unit in BVI was fined $440,000 by island’s regulator. The Wall Street Journal discusses how the British Virgin Islands is dealing with the aftermath of the Panama Papers.

On a visit to Hong Kong and China in October, officials from the British Virgin Islands urged businesses and families to register companies and store assets in their Caribbean isles.

Since April’s “Panama Papers” leak of documents from law firm Mossack Fonseca, that is an increasingly hard sell.

For decades, the British Virgin Islands was a cheap and popular place to set up companies for investments or transactions. But an already fragile reputation for transparency and tax reporting was shaken by allegations that Mossack Fonseca clients used BVI companies to launder money and hide wealth from tax authorities. Mossack Fonseca denies any wrongdoing.

The BVI’s government announced Tuesday the biggest crackdown ever from its financial regulator: A $440,000 fine against Mossack Fonseca’s BVI unit for lax anti-money-laundering and terrorist-financing controls. It said the firm didn’t always check and maintain adequate records of who its customers were. The firm couldn’t immediately be reached for comment.

Along with the fine, the government said the regulator was changing practices to monitor more effectively firms that create companies.

‘People don’t want to be associated with a jurisdiction with a reputational problem. Whether real or unreal, they just want to avoid that association.’

Despite the efforts to improve its standards, BVI is now at risk of losing business to other offshore financial centers.

Companies and rich families in Asia, accounting for around 70% of BVI’s incorporations each year, are among those pulling back from the British territory, according to people working in the offshore financial industry. Data from BVI’s financial regulator show the number of new BVI companies fell 40% between April and June from the same three months last year, accelerating a decline in the past few years as the global economy cooled.

Last month, a BVI company listed in London, Asian Growth Properties Limited, said it wants to move to Bermuda because of the negative publicity from the “Panama Papers.”

“A British Virgin Islands domicile may no longer be suitable for publicly listed companies,” and may present a barrier for investors, it said.

BVI now has to walk a fine line: Bolster its reputation without undermining the anonymity that made it attractive in the first place, doing it before it loses more market share to other popular offshore destinations.

“People don’t want to be associated with a jurisdiction with a reputational problem. Whether real or unreal, they just want to avoid that association,” said Colin Powell, a government adviser on international affairs in Jersey, another British territory that competes with BVI for corporate and wealth business. Mr. Powell isn’t the former U.S. Secretary of State.

The Panama data leak left a deep stain. Politicians, business people and celebrities used companies in BVI and elsewhere to disguise transactions and stash wealth, sometimes for illegal purposes, news reports based on the leaked files alleged. The U.K., Australia and France are among the countries investigating the allegations.

Also damaging: The appearance of BVI companies in other recent scandals including alleged corruption at Malaysia’s 1MDB government fund, and an international bribery case settled last month between Och-Ziff Capital Management LLC and U.S. federal prosecutors. U.S. prosecutors allege officials at 1MDB diverted funds into bank accounts of fraudulent shell companies in BVI and other offshore locales. The 1MDB fund has denied wrongdoing.

In the Och-Ziff case, the hedge fund admitted it paid bribes to officials in the Democratic Republic of Congo through a BVI company.

At stake is BVI’s biggest source of revenue. Registration fees for the 430,000 companies that call it home are worth around $200 million a year, out of total government revenues of $318 million in 2015, according to government figures. Tourism is BVI’s second-biggest industry. Two years ago, the islands started an effort to drum up other types of revenue, such as fees from a planned international arbitration center.

“The appetite is still there for the use of BVI structures,” D. Orlando Smith, the premier of the British Virgin Islands, said in a recent interview.

“BVI continues to be one of the best regulated jurisdictions, ahead of many other countries, even ahead of the U.K. as far as regulations are concerned,” Mr. Smith said, pointing to how information around company owners in the U.K. may be unverified.

For decades, anonymity was BVI’s calling card. Tax authorities, regulators and prosecutors often struggled to establish who really owned a BVI company. Many are owned by other companies in far-flung places such as Belize and the Seychelles, leading to layers of companies with no clear owners.

Now, pressure from international authorities—most notably the U.K. government—means information on BVI company owners and directors will soon have to be stored locally with the 100-plus company agents based on the capital island of Tortola, rather than having the option of keeping the data with lawyers and agents in Hong Kong, London and other hubs. The new system will be up and running next year, the premier said.

Transparency proponents say it is currently too easy for company owners to hide behind lawyers or professional directors, and that having the information on-site will let BVI pass information more quickly to other countries. Most information will continue to be inaccessible to the public and it won’t be held in a central database.

In contrast, the U.K. this year started requiring company owners with more than a 25% stake to disclose their holdings in a public database, but critics say no one is checking the accuracy of the information.

Nipping at the BVI’s heels are stricter, but costlier British territories such as the Cayman Islands, Guernsey and Jersey. Representatives from Jersey Finance, a marketing agency for the island, were in Shanghai and Hong Kong on their own roadshow in October.

By Margot Patrick , WSJ