Arturo Wallace covered the opening of the new canal.

One of the most impressive engineering feats of the 20th Century century, the newly-expanded Panama Canal is now open for business. But why should Barbados and Seattle in particular give thanks to the unique waterway?

It’s been around for so long that it’s tempting to assume everybody knows about the Panama Canal, but let me start with the basics, just in case.

It is the huge waterway that carves in half the little Central American country of the same name, and it has been allowing ships to cross between the Atlantic and Pacific oceans since 1914.

A hundred years ago, when it first opened, it cut travel time between the United States’ west coast and Europe in nearly half, revolutionizing global trade.

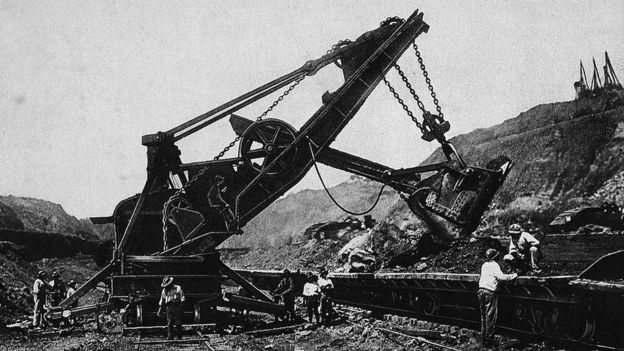

And its construction, which cost tens of thousands of lives, was also a huge engineering feat: one of the biggest and most ambitious building projects ever undertaken.

And guess what? It just got much bigger.

When I crossed it 20-plus years ago, it was already quite impressive – especially the set of locks that slowly raised and lowered our huge cruise ship as it negotiated the isthmus of Panama.

And on the year of its centenary, two years ago, I went back and got to see first-hand the enormous expansion works that have just been completed – Panama’s multibillion bet to make sure the canal stays relevant for at least another century.

The new locks are the size of the Empire State Building, with doors that were built using enough steel for 19 Eiffel towers and walls lined with enough basalt rock for two of Giza’s great pyramids.

As such, they can accommodate much bigger ships: monsters able to carry more than 13,000 containers, whereas previously the biggest vessels the canal could accommodate could carry “only” 5,000 of them.

And, quite fittingly, a massive Chinese container ship was the first to use the new 77 km (48 mile) lane on its way to the USA, symbolically linking the canal’s two biggest users.

It was the US which built the canal, and 65% of the cargo that uses the waterway has American ports as its origin or destination.

But before the expansion some 14,000 ships – connecting some 1,700 ports in 160 different nations – crossed the canal every year, moving a little more than 3% of all global trade.

And now, it has double the capacity.

For Panama this will mean a huge increase on the $2.6bn (£1.9bn) in revenue made just last year, quite a handsome sum for a country with a population of around three million.

The maiden crossing also marked the happy ending of nearly 10 years of works, even though it came among bitter financial disputes, amid huge overruns and warnings that the builders may have compromised its safety by cutting corners.

The Panama government, however, disputes this.

And for most Panamanians, the newly-enlarged waterway is nothing but a source of huge national pride, with thousands gathering on the shores of the Cocoli Locks last Sunday to witness and cheer the occasion.

The country’s identity has been shaped by the canal ever since the United States forced its independence from Colombia in order to make it possible.

But Panamanians only got control of the waterway in 1999.

And they all know the country’s economy depends on the waterway and the industries built around it, including the financial and legal services the world now knows all too well because of the so-called Panama Papers.

Not everybody, however, has benefited equally from Panama’s impressive economic growth during the past decade.

Photo by Joe Raedle

Panama’s wealth is especially evident in the skyline of Panama City, which still dazzles me every time I approach it by air: a collection of skyscrapers and glass towers to compete with Miami’s or Hong Kong’s that feels very much out of place in the southern edge of Central America.

But there’s very little sign of it beyond the capital: one of every three Panamanians is poor, and the figure rises to more than half of those in rural areas.

And one of the biggest challenges facing the Panamanian government is how to ensure the wealth generated by the newly-enlarged canal is spread more evenly.

It is not, however, only Panama which will benefit from the improved waterway.

And it the past is anything to go by, the big winners may end up surprising us.

Indeed, it can be argued that Seattle, in the US northwest, became the technological hub it currently is thanks to the Panama Canal:. By lowering costs it allowed massive amounts of timber produced there to be used on the US east coast.

One of the big beneficiaries of the boom was one William Boeing, who was able to use his profits in the timber trade to sustain a little aviation company. And the rest is history.

But probably the biggest winner of the construction of the original Panama Canal was not Panama or the USA, but the small Caribbean island of Barbados, which provided a significant percentage of the workforce that built it.

That meant lots of money sent back home in remittances, more women entering the local economy, better local wages and the development of a banking system that turned Barbados into one of the Caribbean’s more important financial centres.

And, while Panama currently is the 10th most unequal country in the world, Barbados is the 51st richest country in terms of GDP per capita.

Just another example of why the Panama Canal, and its history, is so fascinating.