For some people, a quick trip to Hawaii or a stay in Panama is a vacation, but it’s just another day on the job for one University of Wyoming professor.

Corey Tarwater has been with the department of zoology and physiology since January but is making big waves, department head Donal Skinner said.

“She rose to the top of an extremely competitive pile of applicants,” he said. “She just fit perfectly here and has such enthusiasm.”

Tarwater’s specialty is the study of year-round resident birds and how they interact with their environment, she said.

“I always knew I wanted to do something with animals,” she said. “I was a wildlife major at ‘UC’ Davis, I had an awesome ornithology professor, and I thought birds are pretty cool. I started off wanting to work with mammals — everyone wanted to, because big cats are awesome. But birds are everywhere, you can watch them, see what they’re doing. People that study mammals, some of them never see what they’re studying — they’re nocturnal and you can’t study behavior.”

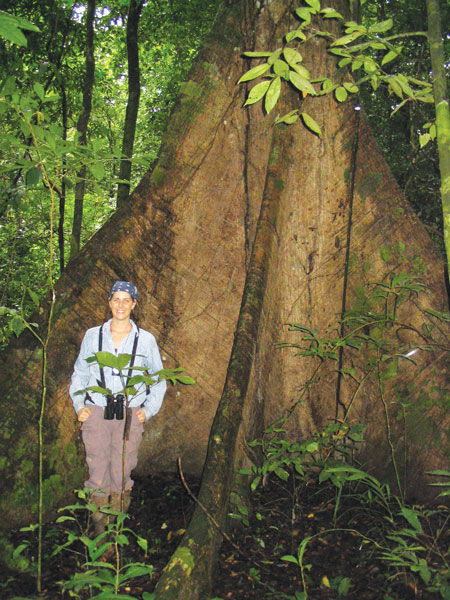

This led Tarwater to her long-term study in Panama, which she began in 2003.

“For my master’s and Ph.D., I spent six-11 months a year there from 2003-2009,” she said. “After I finished my Ph.D., I’ve been going down there for two months a year.”

Birds span across the globe, so Tarwater had her pick of areas and ecosystems to study. The tropics drew her in immediately, she said, mainly because of the broad diversity of flora and fauna.

“The tropics are awesome — if the birds aren’t doing what you want them to do, you always see something cool,” she said. “You see monkeys all the time, you just see weird stuff. Its appealing, if you like being outside and you want to go somewhere you can just see amazing things all the time nobody’s ever studied; the tropics are great for that.”

Forest fracturing is a huge problem in the tropics, Tarwater said, and her studies focus on the effects it could have on Panama’s birds — specifically, insectivores, or birds that eat insects. Fracturing is when a forest is cut up or interrupted by cities or fields, she said.

“(Insectivores) are the first species that go extinct from fragments,” she said. “They’re thought to be more sensitive to climate change and other environmental perversions, but people don’t really know.”

These birds are an important part of an area’s ecosystem, Tarwater explained, as taking away one link could have disastrous effects down the chain.

“These guys are important because they eat insects,” she said. “People have shown that, when you take out these understory insectivores, you have a huge increase in herbivorous insects, and that completely changes the plant community because everything’s being eaten.”

While Tarwater has been working in Panama for more than a decade, she’s ready to bring UW students into the mix.

“I’ve got three undergrads already that are working with the Panama projects,” she said “I promised them they’d come with me to Panama, and I got a lot of volunteers.”

A summer field course for students to study in Panama could be one of the first steps toward a more stable student infrastructure, she said.

Wyoming high school students could even become involved in her studies as well, Skinner said.

“When you’re reaching out beyond the university level into the high school level, it’s just fantastic,” he said. “She’s really going beyond what the average starting professor does.”

The plan is to connect Wyoming high school students with Panama students in a cross-cultural program, Tarwater said.

“The idea is to have this monthly program where we do webcasts and have researchers down in Panama go around with GoPros and show what they’re doing in the field, and high school students here can ask questions.”

Tarwater also brought another project she’s been doing research to UW —with the US Department of Defense about invasive species in Hawaii.

“The reason the Department of Defense is interested is because they have a lot of bases in Hawaii, and they put a lot of money into native plant management,” she said. “They plant them into the field, but in a lot of cases, they’re not sure if they’re going to survive.”

Tarwater is determining if birds affect the dispersal of plant seeds, both native and invasive, and if continual plant maintenance is required for the future.

Efforts to retain and save native plants and forests are important for more than just aesthetic value, Tarwater said.

“Tropical forests are where we get the majority of our medicinal plants,” she said. “Also, if you get rid of the plants, you could be getting rid of the other things people might care more about, like game species. As soon as you change the forest, you’re changing everything that’s in it.”

Skinner said Tarwater and her research are a perfect fit for the department and UW.

“There are quite a few bird researchers here, and that’s one of the reasons why she complements us,” he said. “That’s one of the factors when we were making a hire. She just slots in perfectly.”